victoria to sitka logbook

transcript

On the passage from Victoria to Sitka we traveled 1,800 NM, the journey lasting from May 1st to August 11th 2024. Rek kept a logbook of our travels, to help us remember the conditions we encountered, our thoughts at the time, etc. Sailing near shore, we think, is more difficult than sailing offshore, there are more obstacles to deal with, like traffic, reefs, currents, and land effects on wind.

Our aim was to get near 58°N, the highest we sailed on this trip was 57°N. We wanted to explore Southeast Alaska and the north coast of British Columbia, to experience anchoring in deeper waters, and to see if we could enjoy sailing in colder, rainier weather.

| Week 1 | |

|---|---|

| May 1st | Victoria to Sidney I awoke to an awful sound, an alarm ringing at 0540. Devine had been waking up at 0600 every second day all year to go to the gym, and so was used to this, but I could not find my feet. The morning was rude, I couldn't persuade my body to leave the bed to face it — it had taken us so long to build up this much warmth! I knew that current waits for no one, and so with eyes still closed, my legs crawled out of the blankets, my body inevitably followed, ragdolling out of bed and into the cold. I awoke to an awful sound, an alarm ringing at 0540. Devine had been waking up at 0600 every second day all year to go to the gym, and so was used to this, but I could not find my feet. The morning was rude, I couldn't persuade my body to leave the bed to face it — it had taken us so long to build up this much warmth! I knew that current waits for no one, and so with eyes still closed, my legs crawled out of the blankets, my body inevitably followed, ragdolling out of bed and into the cold.We got dressed, to preserve what little warmth we had left, then made sure that everything aboard was secured for our sail to Sidney. We're always forgetful when we haven't sailed in a while. In the winter, the boat is still, so still that it becomes part of the land. Pino sways at the dock in heavy winds, but nothing threatens to fall over, the motion is never violent. Now, each item must go back to its assigned spot, lashed down. There is light outside at this hour, it helps, but waking before the birds is not right. As soon as we moved outside, Peter, our dock neighbor and good friend, was there to greet us. Peter, like myself, doesn't share Devine's early hour waking habit, but he knew we were leaving, and made an effort to be there to say goodbye. Even at this early morning hour, Peter looked as dapper as ever, Peter, who goes to the gym in corduroy pants and button down shirts. We hug, he helps us push off. |

| Pino glided away from the dock on calm waters, propelled by Calcifer II. Our departure awoke another neighbor, Gunther, he was outside, and he too waved us off, "where are you going again?" he asked. "Alaska!" we whisper-shouted back as we drifted past — it was early, we didn't want to make more noise than necessary. The little ephemeral floating community we'd found was precious, like birds returning to land to nest every year, we all gather in the fall, and come spring, everyone flies away. Some birds return to the nest, others don't, drawn by the allure of distant lands. A light breeze greeted us at the mouth of the outer Victoria Harbour, we hoisted Pino's wings inside the calm of the breakwater. When out in the Juan de Fuca Strait, the body of water that we must cross to get to Sidney, the wind was not strong enough to push us by itself. Calcifer II continued to provide help. |

|

| Last winter, we built our own gimballed stove, we tried it for the first time underway. I toasted bread in our heavy cast iron pan, then coated one side of the crunched-up exterior with peanut butter. While we ate our breakfast, I boiled water to thin the moka pot coffee — doing this fools us into thinking there is more coffee to drink. I passed the grinder to Devine outside who was steering and holding the tiller with one leg. We had modified our tiller head for this trip, it was now low enough that we could steer like this, freeing our hands for other tasks. We bought this wooden tiller at a scrapyard in Sonoma(California) in 2016, when sailing down the west coast of the United States. The head, which binds the tiller to the rudder stock, forced it at an angle that was abnormally high for steering, but the tiller itself was perfect. We rectified the design this year, but only because a crack had formed in the head which forced us to put together a makeshift replacement, consisting of an aluminum pipe, several heavy bolts and bungees. When the water in the kettle was hot, I switched it for the moka pot and completed our breakfast routine. The boat wasn't heeling enough for this to be a good first test for our stove, but the unit performed well. | |

| Victoria is on the south end of a peninsula to the southeast of Vancouver Island, Sidney is on the northeastern end of this same peninsula, 25 NM away. When we turned around the south end of the peninsula, the wind left us, as it tends to do in this area. The wind only ever bends around the corner when Juan de Fuca is in a bad mood. The calm lured out several small fishing boats. We laughed, seeing the number of gulls at their heels. Each boat had its own little gull fan club. Some gulls were resting on the cabin tops, the rest were in the water, paddling around, waiting for scraps or for space to free up on the boat. We wondered if the people on those boats liked the gulls. Were they friends? Did they give them names? Or were they a terrible nuisance? | |

| The wind returned south of James Island, we rode it into Sidney, arriving at 1100. | |

| May 2nd | Sidney to Montague The alarm rang at 0600, we snoozed until 0640, then left at 0800 to catch the current north to our next anchorage. Bing, bang, boom. After pushing off the dock, we pulled onto another to fill 4x20 L bins with diesel — our main fuel tank only holds 62 L, keeping annexes aboard is necessary for long coastal trips. We hoped the wind would be a frequent companion on our trek north. The alarm rang at 0600, we snoozed until 0640, then left at 0800 to catch the current north to our next anchorage. Bing, bang, boom. After pushing off the dock, we pulled onto another to fill 4x20 L bins with diesel — our main fuel tank only holds 62 L, keeping annexes aboard is necessary for long coastal trips. We hoped the wind would be a frequent companion on our trek north. |

The wind was blowing out of the northeast, but we only felt it once past Portland Island. It was coming out of where we needed to go, but as strange as it sounds to those unacquainted with the physics of sailing, a sailboat can work with this. We tightened the sheets and sailed into the wind, tacking as required. Devine read through a thick book documenting Southeast Alaska anchorages, while I, at the tiller, counted cormorants in the water. We saw a group of 30 near Portland Island, with a few gulls amongst them. The gulls were outnumbered, out of place, surrounded by cormorant heads — both were easy to distinguish from afar, because cormorants sink, while gulls float. We played dodge-the-ferries, while tacking northward, until the breeze became too weak to sail with. Calcifer II carried us the rest of the way to Montague Harbour. We arrived at 1300. Tacking had added 3 extra nautical miles to our trip. Sailing into the wind is not the quickest way forward, we can't be in a hurry, but timing matters when sailing in waters governed by strong currents. The current reverses many times per day, when it turns against us, progress is slow, and depending on the strength of the current it can stop our vessel outright. If the wind isn't with us, with a current running, progress is a beautiful dream. Our motor can carry us through some current, but it feels like throwing money into the ocean. In these waters, seeing sailboats motor into the wind, constrained by a short tidal exchange, is common. We played dodge-the-ferries, while tacking northward, until the breeze became too weak to sail with. Calcifer II carried us the rest of the way to Montague Harbour. We arrived at 1300. Tacking had added 3 extra nautical miles to our trip. Sailing into the wind is not the quickest way forward, we can't be in a hurry, but timing matters when sailing in waters governed by strong currents. The current reverses many times per day, when it turns against us, progress is slow, and depending on the strength of the current it can stop our vessel outright. If the wind isn't with us, with a current running, progress is a beautiful dream. Our motor can carry us through some current, but it feels like throwing money into the ocean. In these waters, seeing sailboats motor into the wind, constrained by a short tidal exchange, is common. |

|

We arrived in Montague Harbour, a large anchorage on Galiano Island that can host hundreds of boats, dropping our anchor in 11 m(35 ft). The bay hosts several local boats on moorings, but was otherwise empty. Despite there being large areas free of anchored boats, a large motor boat came into the anchorage, 20 minutes after we had arrived, and dropped their anchor very near ours. Pino is a shiny lure, drawing the attention of bigger fish. Inside the cabin, we picked up a few disobedient items that had rolled out of their berths. Some items had found the floor, "this isn't your room," I said, remembering the classic line said by Tom Hanks to a dog in Turner and Hooch — sometimes I fear that too many of my words are borrowed from films. Inside the cabin, we picked up a few disobedient items that had rolled out of their berths. Some items had found the floor, "this isn't your room," I said, remembering the classic line said by Tom Hanks to a dog in Turner and Hooch — sometimes I fear that too many of my words are borrowed from films.We prepared basmati rice with sauteed sweet potatoes, tofu, and greens, seasoned with soy sauce and mirin, with a side of miso soup. |

|

| That night, we continued reading The Martian by Andy Weir. In the book, Mark Whatney must be self-sufficient, he must ration his food to survive. With our upcoming trip, we don't have to ration, our time away from others won't span 4 years, but we do need to be cautious with both food and water. At sea, Pino must be an island. | |

| May 3rd | Montague The wind was too light to sail, so we waited in Montague for an extra day. Avi sent us a message, asking if we'd like to go see the Recycling Center's new plastic crusher and press. We rowed Teapot to shore and met Avi at the dinghy dock, he gave us a ride to the Recycling Center. |

| The new machines transformed plastic waste into new materials, which locals could use to produce art, for construction, or to make replacement parts at home. Same type plastics were gathered — polypropylene, polystyrene, etc. The shredder reduced the plastic into smaller pieces, and a separate machine, a heated hydraulic press, softened and merged the bits into a solid sheet. The size of the sheet depended on the amount of shredded plastic, and the sheet thickness(adjustable with the press). Mixing different colored plastics resulted in a gorgeous mandala daubed with bright and glaring patterns. Ading a single shredded bottle of yellow mustard created amazing contrast. The sheet of plastic ressembled a painting, born of plastic waste. Previously, Galiano Island was exporting all of its plastic waste to the Vancouver mainland, a lot of it now stays on the island, given a second, and hopefully lasting purpose. The recycling center was across from a building that accepts second hand goods, all from residents of Galiano. The center separates all recyclables so they are better processed — just like in Japan. The rest of British Columbia doesn't discern between different kinds of plastics, it also doesn't recycle glass... which is... insane. |

|

| May 4th | Montague to Secretary Islands 0830 departure from Galiano Island, with the goal of stopping either at a bight between the Secretary Islands, or at Clam Bay, a short 10 NM sail away. We needed an anchorage that offered protection from both the SE and NW — a difficult find in these waters, given the fact that most bays have either a SE or NW orientation. Montague fits that description, but it was too far south, we wanted to be near Porlier Pass to exit at slack current come morning. The Gulf Islands are surrounded by natural barriers, rapids that prudent sailors ought to take at slack tide, during the calm between the reversal of the current. All of the rapids open onto Georgia Strait, a large body of water that separates Vancouver Island from the mainland coast. 0830 departure from Galiano Island, with the goal of stopping either at a bight between the Secretary Islands, or at Clam Bay, a short 10 NM sail away. We needed an anchorage that offered protection from both the SE and NW — a difficult find in these waters, given the fact that most bays have either a SE or NW orientation. Montague fits that description, but it was too far south, we wanted to be near Porlier Pass to exit at slack current come morning. The Gulf Islands are surrounded by natural barriers, rapids that prudent sailors ought to take at slack tide, during the calm between the reversal of the current. All of the rapids open onto Georgia Strait, a large body of water that separates Vancouver Island from the mainland coast.The Secretary Islands anchorage was on the way to Clam Bay, we had never been there, but we would go by to check it out, to see if it was suitable for an overnight stay. |

| We had 5-10 kn on our bow the entire way, but it lessened as we neared our destination. The small bight between the Secretary Islands was open to the north, and we suspected that northwest winds could creep in through Porlier Pass to disturb it, but we decided to chance it. We set our anchor in 6 m (20 ft) of water, in mud. The stronger gusts were curling around the corner, entering the anchorage. The winds later rose to 15-20 kn, but would lessen before dying entirely. It was supposed to turn to the southeast overnight, and to build up come Sunday morning into a strong enough breeze to carry us across the strait. It was likely that we would have endured these same wind conditions in Clam Bay. Clam Bay, a bay tucked between two islands, is full of debris, old crab pots, disused aquaculture gear, it is not our favorite spot. The unnamed bight in the Secretary Islands was a welcome change. |

|

At 1400, the forecast was upgraded to a strong wind warning, with 20-30 kn blowing in the strait — not a fun surprise. The anchorage became more rolly, with the boat yawing with the coming waves. We both felt sea sick. Like before, only the strong gusts penetrated our little bight, but the waves were sneaking around the corner, invading our space. Devine took a nap, working on the computer in these conditions was too difficult. I wanted to nap too, to rid myself of a headache, but I preferred to keep watch.  |

|

| Later, the forecast changed yet again, down to 15-25 kn. The motion at anchor became tolerable, cooking dinner without fear of feeling sea sick would be possible. I cooked some sticky brown rice with a topping of sweet and sour chickpeas with crushed peanuts on top. The wind was howling in the strait, but it wasn't felt as strongly here. The wind left entirely at 1700, allowing us to sleep well. We are always grateful when the wind goes to sleep too. | |

| May 5th | Secretary Islands to Smuggler Cove We awoke to an even quieter quiet. A lonely log drifted past, a bald eagle sat atop a bare tree top, a dog barked, the echo distorted the bark of the dog, making it appear like it belonged to a larger, more ferorious animal. We left our unnamed nook at 0830, motoring towards Porlier Pass to catch it at its quietest. Porlier Pass can run fast at peak current, but like all rapids, when timed right, the waters are smooth. Today, the waters were undisturbed. We passed a log supporting 12 black-headed gulls, we named them: the black-headed gull syndicate. This log was the place to be, this is where shady decisions in the black-headed gull world happened.  A small fishing boat idled in the pass in the shallows, we glided past them, hoping to find a rippled sea in the strait. Ripples were indicative of wind. The forecast had been unreliable, what was supposed to be 10-15 kn out of the southeast, turned into wind that was supposed to die entirely at 1000, not long after our exit from Porlier Pass. Wind was forecast in the north part of Georgia Strait, so we thought we'd go out and find it. We spotted a band of darker water on the horizon, there was wind out there, but we had to push further away from the shore to reach it. We met with the rippled band of water, hoping that it would stay rippled, it did, with many more bands ahead. A small fishing boat idled in the pass in the shallows, we glided past them, hoping to find a rippled sea in the strait. Ripples were indicative of wind. The forecast had been unreliable, what was supposed to be 10-15 kn out of the southeast, turned into wind that was supposed to die entirely at 1000, not long after our exit from Porlier Pass. Wind was forecast in the north part of Georgia Strait, so we thought we'd go out and find it. We spotted a band of darker water on the horizon, there was wind out there, but we had to push further away from the shore to reach it. We met with the rippled band of water, hoping that it would stay rippled, it did, with many more bands ahead. |

| Our plan was to skirt along the length of Galiano Island, if the wind did not manifest we would duck into Gabriola(another island, further north). The wind stayed, so we pushed on. 10-15 kn winds out of the southeast carried us all the way across. The wind did lessen at times, but it always increased again to fill our sails. The day started grey, and stayed grey. Our new rain jackets saw their first rain today. Our former foulweather gear would get wet and stay wet, making any sail in the rain uncomfortable, while our new vinyl bibs and jackets kept us dry. Although, keeping our hands dry and warm at the same time was a problem. |

|

| It was difficult to see the Vancouver mainland with this rain. In the absense of a visual reference, we had to follow our compass. We took turns steering Pino. When we spend long days on the water we have to give the other time to rest, to warm up. Most Alaska-bound sailors favor boats with enclosed cockpits, but Pino's cockpit is always exposed to the weather. The rain, the sun, and the wind always find us. Both of us were dry today, but it was cold, we hadn't layered on enough clothes. | |

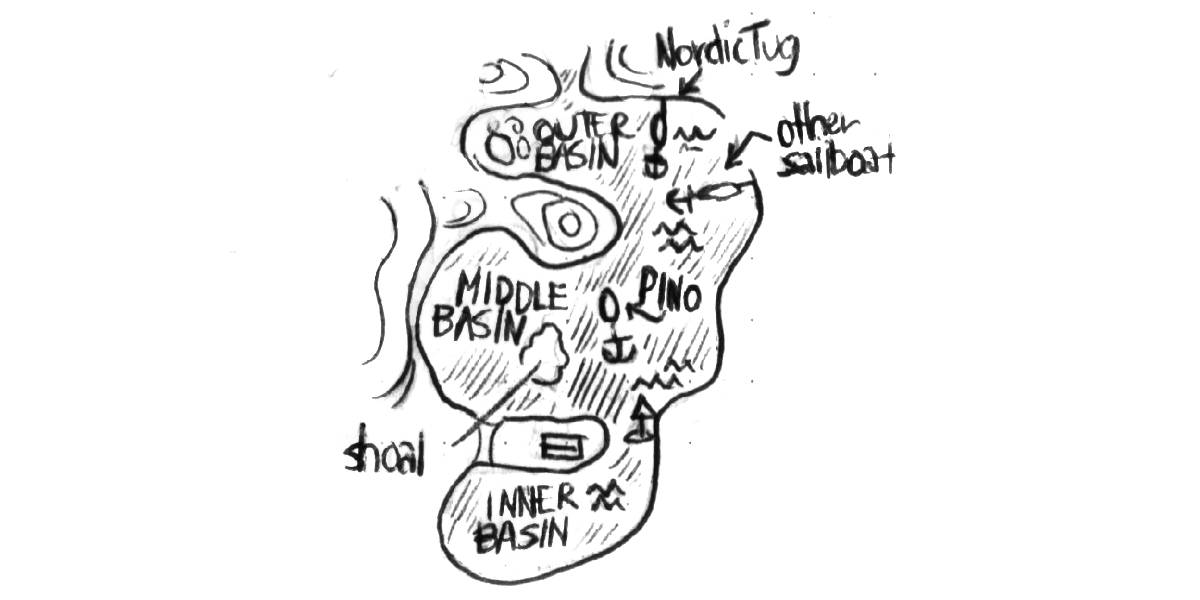

| When we arrived at the entrance to Smuggler's Cove it was 1600, both of us were spent, our defenses eroded by the prolonged exposure to the rain and cold. In such conditions, our bodies have to work extra harder to keep us warm, burning more energy. "My tank is low." Just as I'd said this, the rain increased, bringing the morale onboard to a newfound low. We dropped the hook in the middle basin, not bothering to stern-tie to shore. Devine fired up the woodstove while I secured gear in the cockpit and on deck, determined not to have to go back out there once I tasted the warmth of the cabin. We ate a hearty rice noodle soup, it warmed our insides, while the woodstove took care of our outer shells. Our plan for tomorrow was to go to the grocery store in Pender Harbour. In our haste to leave Victoria, we forgot to stock up on a few key ingredients, like olive oil, and balsamic vinegar. The grocery store there, we knew, had excellent baguettes in stock. A singlehanded sailor came into the anchorage at 1900, he decided to stern-tie, even if there was room, even if it was raining buckets.  |

|

| May 6th | Smuggler's Cove to Pender Harbour The wind kept us awake last night. Southeast winds funnel through Smuggler's Cove. Our swing radius was very limited in this bay, when the anchor rode was taut, we were 18 m (60 ft) away from the shore. We assumed a southeast wind would point us toward the outer basin. Swinging that close to shore doesn't ever stop being worrisome. We were awake from 0100 to 0400. After 0400, the wind lessened, our anchor watch was over, we fell asleep. |

| We woke up at 0700. We've experienced big weather while anchored in this bay before, but whenever a detail changes, like anchoring somewhere new in the same bay, it is difficult to have complete trust. Our boat is infinitely valuable to us, sleeping badly is a small price to pay, and we can catch up on sleep later. We could see our own breath because of the cold. We prepared whole wheat pancakes for breakfast, while firing up the woodstove. |

|

| We left Smuggler's Cove at 0930, riding the tide north to Pender Harbour, a short 10 NM hop away. The sun came out during our transit, warming our bodies, a reminder that the world could be warm, that it could have color in it. Some clouds drew shapes on Texada Island, while others, heavy with water, threatened to burst. We spied a large cloud with a skirt of rain, south of us, the wind was helping it along, it too had Pender Harbour in sight. We hoped to arrive before it reached us. | |

| Pino found a spot on the Pender Harbour public dock at 1130. We went to pick up a few items at the grocery store. "Where are you going?" The captain of a Nordic Tug asked us. "North." We said. "Us too!" | |

| May 7th | Pender Harbour to Ballet Bay The plan was to skip north to Ballet Bay on Nelson Island, if the wind cooperated we would try to ride it up to an anchorage further north. We always leave with backup anchorages in mind, some for if the wind is helpful, others for if it isn't. The plan was to skip north to Ballet Bay on Nelson Island, if the wind cooperated we would try to ride it up to an anchorage further north. We always leave with backup anchorages in mind, some for if the wind is helpful, others for if it isn't.We forgot to buy a small axe while in Victoria, we considered looking for one in Pender Harbour but there were no hardware stores within reasonable walking distance — much of British Columbia is car-centric. We hope to find one in Port McNeill, a city near the top of Vancouver Island. We would use the axe to split our own kindling for the woodstove, wood sold in stores is usually not sized for our little 23x23 cm firebox. Mornings are still very cold aboard Pino, we run the woodstove to stay comfortable. |

| We left the dock at 1000. The wind funneled into the Harbour, a sign that there was a lot of weather out there. We put a reef in, beating to weather under a full sail can get really sporty. We inched out of the Harbour by motor, and sailed as soon as we cleared the outermost island and begun a seemingly infinite succession of tacking, with one coast fading away while the other came into focus. On each tack, our eyes found a landmark to aim for across the channel. Every lighthouse, old cannery, cliff face or clear-cut area on a mountain, acted a a marker and a proof of our progress. We had to tack 6 times to line up with the entrance to Ballet Bay, our planned anchorage of the day. |

|

| We saw two other sailboats on the water today. One of them, a catamaran, beat us to our anchorage, while the other sailed on. At times, we were going at 6 kn, a fine speed under a reefed mainsail. The boat was heeling to 20 degrees, a good test for our gimballed stove. We have used it everyday since we left. | |

| Once we arrived into Ballet Bay, we saw that the catamaran had claimed the shallows, but we found a spot nearby in 13 m (45 ft, 16 m / 55 ft at HW). The northwest wind found its way into the bay, but there were no waves at least. We prepared sandwiches with a baguette we picked up in Pender Harbour. I was glad to have waited to arrive to eat, some meals are unpleasant to eat underway. When the wind and the waves are up, I feel like I have to finish the meal in a hurry, I don't get to enjoy it. I want to enjoy my sandwich. I will enjoy my sandwich! |

|

| Week 2 | |

| May 8th | Ballet Bay to Sturt Bay After partaking in another round of delicious sandwiches for lunch, we got ready to hoist the rode and anchor. In 13 m (45 ft) of water, all of the chain rode is out (we have 30 m / 100 ft of chain aboard), with a good length of rope rode hanging in the deeps. Pino does not have a windlass aboard, we haul everything up by hand, or by using a chain hook and leading a line back to a cockpit winch. The chain stopper at the bow locks the chain, permitting us to adjust the chain hook safely. We can't use the same technique for the rope rode, though. Up until now, we did it by hand, but that won't be possible in depths greater than 18 m (60 ft), which we'll likely encounter up north. Our plan was to tie a prusik knot around the rope rode to haul it in (read more about it in no windlass). After partaking in another round of delicious sandwiches for lunch, we got ready to hoist the rode and anchor. In 13 m (45 ft) of water, all of the chain rode is out (we have 30 m / 100 ft of chain aboard), with a good length of rope rode hanging in the deeps. Pino does not have a windlass aboard, we haul everything up by hand, or by using a chain hook and leading a line back to a cockpit winch. The chain stopper at the bow locks the chain, permitting us to adjust the chain hook safely. We can't use the same technique for the rope rode, though. Up until now, we did it by hand, but that won't be possible in depths greater than 18 m (60 ft), which we'll likely encounter up north. Our plan was to tie a prusik knot around the rope rode to haul it in (read more about it in no windlass). |

| This is not the fastest, or easiest method of hauling an anchor rode, but it works. Today, the wind was light, the water not too deep, we hoped it would continue to work well in more difficult conditions. Winches provide excellent mechanical advantage. A determined sailor could lift an anchor by way of a 4:1 pulley system alone, a technique rescuers use, but winches are present on most boats our size. Motor boats too could benefit from having a winch onboard, especially in the event of a windlass failure, or to pull in a stern line in heavy winds. We've seen boats failing to secure their stern lines with wind on the beam because they lacked the strength to pull the line in by hand. | |

| After hauling all of the rode back on deck, we motored out of Ballet Bay to a calm Malaspina Strait. The forecast called for 5-15 kn out of the northwest. Sometimes this means 5, other times 15, but it is usually zero. I spied a dark blue band on the water ahead. "Either that's wind, or a tide line," I said, grabbing the binoculars, "Wind! Lots of it!" We raised Pino's wings, entered the blue band, and sailed, sailed, sailed! Then, shortly after, we reefed, reefed, reefed, because the wind was stronger than 15 kn(we cannot offer precise readings, because our wind meter died a long time ago). As we reefed the main, we accidentally heaved-to, which sent a few loose items rolling in the cabin. | |

| We zigzagged up Malaspina Strait. The wind lessened as we neared Sturt Bay on the northeast end of Texada Island. While moorage on this coast keeps increasing, the dock fees for the modest facilities at the Texada Boating Club continue to be reasonable, but we decided to try anchoring in the bay north of the docks for the first time instead. We later learned that the bottom was fouled with old logging gear. Texada Island's industry, consisting of both logging and mining, has mostly disappeared, but scars remain. Many bays on this coast are fouled with old machinery, we often see rusty cables and gear on land when hiking, posing as roots, half-buried in the soil and ferns. | |

| We had Japanese curry for dinner, using up two whole potatoes that had begun to sprout. These days, we move everytime there is wind, even if it's weak. In the summer, a forecast of 5-15 kn will often mean no wind, but if the same numbers are forecast in the spring, the higher number is often more accurate. So far, we have sailed almost everyday. This was very different from the kind of sailing we'd done in these waters these past 4 years. We usually enjoy staying in the same anchorage for days, or weeks at a time. We will have to slow down once we arrive near open waters, stronger weather may not allow us to sail everyday — I am getting ahead of myself, eyes on tomorrow, Rek, eyes on tomorrow... well, eyes on tonight! I look forward to continuing to read The Martian. Mark Whatney is sprouting potatoes, just like us! | |

| May 9th | Sturt Bay to Galley Bay We woke up at 0600 to another calm morning, a quick look outside revealed that this quiet was contagious, it had spread to the whole of Malaspina Strait. We woke up at 0600 to another calm morning, a quick look outside revealed that this quiet was contagious, it had spread to the whole of Malaspina Strait. |

| Underway, Devine made modifications to our rain jackets, the jackets were new, but the strings used to tighten the hoods down over our heads weren't equipped with stoppers. On our last rainy transit across the Georgia Strait, we both complained about the lack of stoppers on our hoods. When sailing, a tight hood won't catch in the wind, keeping our vision clear to better see floating debris, whales and traffic. Devine harvested two stoppers from our older foul-weather jackets. The jackets each had 2 stoppers on the bottom, but we never used them. The only thing that these stoppers were good for was for getting caught in the cabin table when walking inside. Our table has an extension — bound to the main part of the table by a piano hinge — that we fold down when underway. The stopper on my jacket liked to get caught in the hinge between the two halves. "Everytime!" I'd say aloud, annoyed, reaching back to free it. Never again!  Both of our jackets were awarded hoods with stoppers! Sometimes it feels like the items we buy haven't been well-tested by their makers. Had they thoroughly worn our jackets, they too would have realized that stoppers were necessary. Devine sure enjoys fixing things underway. Both of our jackets were awarded hoods with stoppers! Sometimes it feels like the items we buy haven't been well-tested by their makers. Had they thoroughly worn our jackets, they too would have realized that stoppers were necessary. Devine sure enjoys fixing things underway. |

|

| On this long transit, whenever Devine, who'd been inside fixing things, would peek outside to look at our progress northward and say "Lund!" while gesturing to whatever was out there. Of course, it took Devine 3-4 more tries before Lund finally did materialize. In Pino lore, saying Lund aloud enough times toward the land will eventually turn said land into Lund. Lund is a small port very near to Desolation Sound when leaving Sturt Bay, once you reach it the land of quiet and beautiful anchorages is near. We have never been. |

|

| When arriving in Desolation Sound, a place that does not wear its name well in the summer, beautiful mountains appear. This early in the season, the mountains are covered in snow, adding to the majesty of the scenery. Snow to the peak of a mountain is what a crown is to a human head. We tucked into Galley Bay — a place, like Lund, that used to house a commune, now lined with summer homes. The bay appeared very restricted, hostile, with much of the barnacle-encrusted shore exposed at low tide. We were alone, it would have been shocking to find another boat here at this time of the year, Galley Bay serves as overflow parking when the popular anchorages are busy. We had picked this anchorage because... 1: We'd never been. 2: It was near Refuge Cove, our next stop. 3: It offered reasonable protection from prevailing winds. |

|

| We spotted some surf scoters, with their swollen, bright orange bills, swimming near a dock that afternoon. There were many of them moving together in a tight group. "Another entry for bird bingo," I said, it was the first time we had seen one outside the pages of a book. At high water, the bay took on a friendlier, more welcoming appearance. | |

| May 10th | Galley Bay to Refuge Cove We shut the companionway screens before dark, but the mosquitoes were out early, they made it inside and waited. They sent their first agent at 0200, while we slept. It eluded us at first, we both got out of bed to find it. Another agent surfaced later, determined to rob us. We terminated 2 more that night, and another 2 come daylight. Each had left their mark on our walls, a red smear, a reminder that they had in part succeeded. We shut the companionway screens before dark, but the mosquitoes were out early, they made it inside and waited. They sent their first agent at 0200, while we slept. It eluded us at first, we both got out of bed to find it. Another agent surfaced later, determined to rob us. We terminated 2 more that night, and another 2 come daylight. Each had left their mark on our walls, a red smear, a reminder that they had in part succeeded. |

| The plan today was to head to Refuge Cove, a short distance away, to refill a 20 L bin with diesel. There weren't many convenient fuel stops north of Refuge Cove, we wanted to make sure we had enough for our transit through the many rapids up north. The fuel dock was only active 3 days a week at this time of the year, for 3 hours. | |

| We left Galley Bay at 1030. I hauled up most of the anchor rode by hand, but we used the cockpit winch and chain hook to pull in the remaining 15 m (50 ft). Hauling chain up this way stains the deck, especially if anchoring in mud. After engaging the chain stopper, I had to walk back to the block, which was as far as the chain hook could go on deck, I then unhooked the chain to drag it back, mud and all, into the locker at the bow. Most sailors would find this setup less... than ideal. | |

| We glided over to Refuge Cove, a short 5 NM sail, arriving at noon. The docks were empty, we had lunch while waiting for the dock attendant to arrive and operate the fuel pumps. Around 1300, many small boats started to pile in. "You hurt yourself?" The fuel dock attendant asked me, pointing at the blackout tattoo on my forearm, thinking it was a compression sleeve. "It's a tattoo," I corrected him. His face took on an amused, but bewildered expression. | |

| That evening, the only other vessel on the docks was a large supply barge, carrying a giant propane tank to resupply the marina for the coming season. We watched the entire re-supplying process. The local store was also busy unpacking boxes of food, organizing them on the shelves. Being here out of season and all seeing this was neat, like watching a restaurant kitchen before opening hours. | |

| When heading north, there are several paths to take, but all eventually lead into Johnstone Strait, a 110 km (68 mi) long channel known for its traffic, its fast-flowing waters, and for its daily strong wind warnings. The weather in that strait did not inspire an early visit, it was still blowing 35 kn, we instead chose to take the back route, via the Yuculta and Dent Rapids. We planned to cross the rapids on the 12th of May, until then we had time to waste. Why the 12th? Because the turn to ebb was at a reasonable hour on a neap tide. Neap tides are the lowest tides of the lunar month, occurring in the second and fourth quarters of the moon. At this point in the lunar cycle, the tide's range is at its minimum, making it an ideal time to traverse through fast-flowing rapids. A small tide reduces the speed of the current. | |

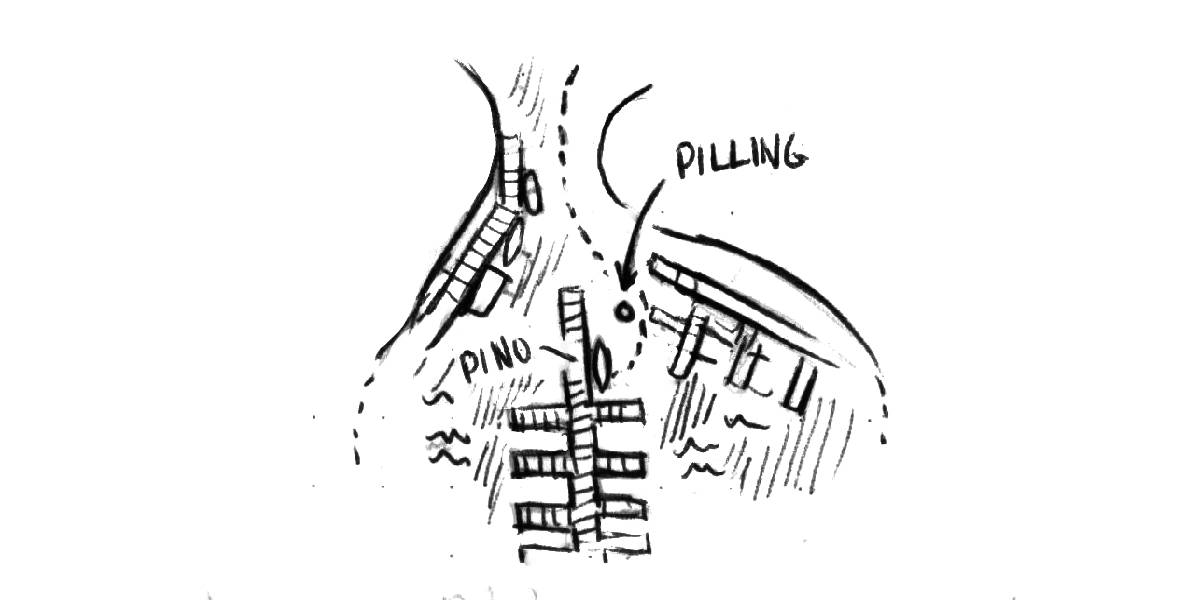

| May 11th | Refuge Cove to Frances Bay Our dock neighbors, 5-6 purple martins, woke us up early this morning. The dock owners installed birdhouses on the top of every pilling, the purple martins were enthusiastically occupying them all, no vacancies. Our dock neighbors, 5-6 purple martins, woke us up early this morning. The dock owners installed birdhouses on the top of every pilling, the purple martins were enthusiastically occupying them all, no vacancies. |

| We pushed off the dock at 0800. The wind was already up and slowly creeping in through Refuge Cove. We reefed the main and proceeded to sailing up Lewis Channel. The wind often blows down from this channel, funneling at its narrowest point, making for an exciting time on the water. We sailed, close-hauled, tacking from one side of the channel to the other, until the wind ran out of breath and we pulled into Frances Bay. By then, both of us were snacking on peanuts, tired and hungry. We arrived at 1400, 22 NM later. | |

| Frances Bay was very breezy, it appeared sheltered from weather on a chart, but the wind came speeding down the hills and into the anchorage. This anchorage was not ideal but it was near the Yucultas, there aren't many options for overnighting safely in the area, all are inconvenient for different reasons. One is littered with old logging equipment that can foul your anchor, another is subject to outflow winds from a nearby inlet at night... | |

| Low tide exposed old and abandoned logging equipment along the shoreline. While Devine steered us to the head of the bay, I prepared a trip line for our anchor. Rusty equipment ashore often means rusty equipment in the water, a trip line ensures that we can retrieve the anchor if ever it did get stuck. I tied the line to the crown of the anchor(many anchors have a hole pre-drilled for this, Rocnas have one). The fender squeaked and shifted uncomfortably as I tied the other end of the trip line onto it, as if to say, "you have got to be kidding!" The fender recalled the time we used it and 2 others of its kin to buoy our anchor chain while in French Polynesia. The 3 fenders were submerged, hovering in the depths, preventing the chain from getting caught in coral on the ocean floor. Today, the fender would not be submerged, it would stay on the surface, keeping our trip line afloat. I threw the fender overboard, we watched it drift away, marking the spot where our anchor lay. | |

We found 2 giant ants aboard today. They likely climbed in while we were docked in Refuge Cove. We hoped we wouldn't find more, they better not be the sort that like to chew through wood, Pino is fibreglass, but the interior is all wood. My arms were tired from the relentless tacking, but despite the soreness, I was glad that the wind had come. My arms were tired from the relentless tacking, but despite the soreness, I was glad that the wind had come. |

|

The strong gusts in this anchorage were very anxiety-inducing. Doodling and writing helped to combat this, but that doesn't help when I'm trying to sleep. Anxiety balloons in the dark.

|

|

| May 12th | Frances Bay to Shoal Bay As expected, we slept very poorly last night. The wind did not let up. The wind rolled down the hills, like an out-of-control train coming to smash up against the shore. As expected, we slept very poorly last night. The wind did not let up. The wind rolled down the hills, like an out-of-control train coming to smash up against the shore.Both of us were awake when the alarm rang at 0500. We took the bed apart, got dressed, and went out to haul in the anchor rode. I don't think I will ever get used to hauling the anchor 5 minutes after waking. Our anchor did not get snagged on anything, we retrieved our fender, the tripline, and moved out of Frances Bay. We raised the main, but the wind decided to stop as soon as we finished hoisting it up. "You kept us awake all night, and now you won't help us out of this anchorage? Thanks for nothing wind!" Pino moved, without the help of the wind, towards Habbott Point at the south end of Stuart Island, where the Yuculta rapids begin. We would have to traverse 3 sets of rapids today, all one after the other. The first on the line is the Yucultas, then Gillard Passage, and finally the Dent rapids (see Yuculta and Dent Rapids for more information). |

| I had entered waypoints on Navionics(a navigation software, that we use along with our chartplotter), to map out the location of all of the eddys that would permit us to make progress through the last of the opposing ebb current in the Yuculta rapids. When northbound, the tactic is to arrive earlier to catch slack tide at the most turbulent point, Dent Rapids, but that means working against some current by riding eddys to get there. We chose to transit on a neap tide to lessen the amount of current we'd have to fight. We rode eddys, the water was disturbed, but not overly so. Once we arrived at Gillard Passage, we had more current to power through, especially at the narrowest point, but it was less than 1 kn. We arrived at Dent Rapids later than we had planned(15-20 minutes later), but we didn't have any trouble. On anything but a neap tide, arriving late would have been costly. For a slow boat, going through all 3 rapids is ambitious, but not impossible provided that the timing is good, that the moon isn't too full and that the sailor is aware of the locations of the eddys in the area. After passing the dreaded Dent rapids, we celebrated with a warm cup of coffee. Passing over a marking on a chart with a whirlpool named "Devil's Hole" was not reassuring, but this dreaded spiral only forms on a large flood current. We read of an attempt by the Spaniards(1792) to transit these rapids. Indigenous villagers had warned them not to run the rapids in their schooners, the Mexicana and the Sutil, they went through and one of the boats got sucked into a whirlpool and was spun three times (read more about the story). |

|

| The wind was up, we slipped on our tuques, scarves and gloves to keep warm, doing our best to finish the hot beverage before the cold got to it. The ride after the Dent rapids was problem free. Cordero Channel, after the rapids, was surrounded by big mountains. At the end of the many long arms branching from the channel, the mountains rose even higher. | |

| We arrived in an anchorage named Shoal Bay, surprised to find many boats on the government dock. We had difficulty squeezing in between two boats — Pino doesn't parallel-park very well. Once Pino's hips got closer to the dock, I threw the end of the boat hook onto the arm of a swimming ladder and pulled us in the rest of the way. Moorage at Shoal Bay dock was cheap, but popular, even in the shoulder season. |

|

| Shoal Bay was idyllic. When the clouds parted late in the evening, the sunlight set the ashen-hued scenery ablaze, painting trees green, carving details in the mountains. The 20-30 kn winds in the strait did not disturb our waters, the lion roared, but not a single blade of grass stirred. | |

| May 13th | Shoal Bay to Forward Harbour We awoke before our 0600 alarm, a crow had landed in the cockpit. "Wake up!" it cawed, "time to go! Time to go!" We left the dock 20 minutes after waking. This was our life now, we couldn't linger anywhere long enough to see a place in all of its moods. We awoke before our 0600 alarm, a crow had landed in the cockpit. "Wake up!" it cawed, "time to go! Time to go!" We left the dock 20 minutes after waking. This was our life now, we couldn't linger anywhere long enough to see a place in all of its moods. |

| We pushed against some current before Green Point Rapids to be there before slack in order to arrive at yet another set of rapids, Whirpool Rapids, 12 NM away, when it isn't running at peak current. Slack tide falls at the same time for both of these rapids, passing them both in calm waters would not be not possible for us. Pino the slow boat wasn't going to bridge 12 NM in less than 2 hours. We passed Green Point Rapids at 0730, with slack at 0754, we had planned on arriving earlier but the opposing current had slowed us down. The rapids opened onto Chancellor Channel, the current there soon turned in our favor, adding to our speed. We were glad for the help, because once past Tucker Point the wind from the strait penetrated the channel, blowing strongly in our faces. By the time we arrived at Whirlpool rapids, it was way past slack tide, there would be some current. "We're still on a neap tide," I said, "it's safe to assume that the current running there will not exceed 3 kn?" When nearing the narrowest point of the channel, looking through binoculars, we saw no dangers so we proceeded through. We started at 4.5 kn, then accelerated to 8.6 kn. "The current maybe did exceed 3 kn after all. 4 kn it seems like," Devine said with a grin, Devine who greatly enjoyed the rush of a sudden and brief increase in speed. We had read that running these rapids at higher current wasn't dangerous, because unlike the Dents, the channel was free of obstructions. |

|

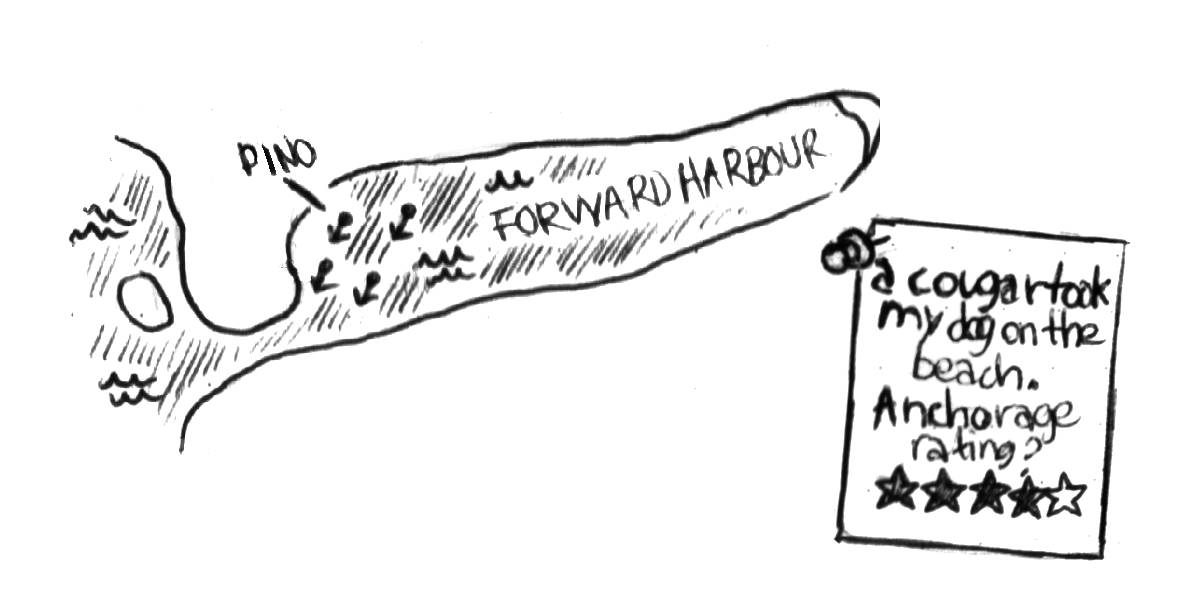

We arrived at Forward Harbour at 1030, anchoring in Douglas Bay in 10 m (35 ft, 12 m / 41 ft at HW). On Navionics, we saw a disturbing review, that we both hoped was a joke, rating the anchorage 4/5 stars despite the fact that a cougar had taken their dog on the beach.  |

|

| Forward Harbour was our last anchorage before entering Johnstone Strait. As I have already mentioned, there are many back channels when heading north, but eventually, all boats, no matter what path they choose to take, end up in the strait. Sunderland Channel, laying ahead of us, was the last back-channel exit when northbound. When heading north through Johnstone Strait, the prevailing wind is from the west(in your face), if a boat rides an ebb current north, then a strong westerly wind blowing against a fast-flowing ebb will generate large waves. Every knot of current is the rough equivalent of 10 kn of wind, a sailboat sailing into a strong headwind in Johnstone Strait with a strong ebb current will face waves that are out of proportion to the conditions. |

|

| The clouds dissipated later in the afternoon, the coming warmth helped revive us. We raised our flip phone up the mast to improve our internet reception. | |

| Every day around 1600, we discussed the next day's transit, we checked the weather, went through our guidebooks, read about the hazards we might encounter, poured over charts, and made backup plans if ever the weather changed or if it didn't allow us to get to where we had planned to go. Tomorrow's wind was ideal for dipping our toes into Johnstone Strait for the first time. Forward Harbour was an okay stop, but the wind curled around the corner, putting all of the boats anchored near Douglas Bay stern to shore for a while. |

|

| May 14th | Forward Harbour to Port Neville As was tradition on board, we got up at 0600. The forecast hadn't changed, we were expecting 15 kn out of the west-northwest. We motored to the entrance to Sunderland Channel, hoping to arrive at the junction leading into Johnstone Strait for 0930, near slack, to avoid some tide rips that form there when the flood tide turned to to ebb. We sailed out on a flood, if there was wind, working against the last of an opposing current in this channel wasn't a big deal. As was tradition on board, we got up at 0600. The forecast hadn't changed, we were expecting 15 kn out of the west-northwest. We motored to the entrance to Sunderland Channel, hoping to arrive at the junction leading into Johnstone Strait for 0930, near slack, to avoid some tide rips that form there when the flood tide turned to to ebb. We sailed out on a flood, if there was wind, working against the last of an opposing current in this channel wasn't a big deal.We flew, flew, flew! The wind was up, blowing out of where we need to go always, but we made good progress. We tacked back and forth, dodging islands, reefs, and orcas. Yes! We saw a pod of orcas with a baby while sailing here! They surfaced near us, we diverted but had plenty of time to take in their features. Everytime they surfaced, we would greet them with an overenthusiastic, "oh wow, oh wow, oh WOW!" Orcas are so beautiful, and the presence of a youngling warmed out hearts. |

| Because we were nervous about today's transit, we didn't have coffee or breakfast. Sometimes the weather changes suddenly, forecasting meaner, more difficult conditions. The ride got more and more sporty as we neared the mouth of the channel. As expected, we had some good wind waves, but our timing for our arrival at Tuna Point was good. We tacked our way forward, the increase in wind allowed us to point higher. We crashed into the larger waves, with spray washing over the bow. | |

| When nearing Port Neville, we encountered more orcas! Again, they stayed close — such lovely creatures. By the time we arrived at the entrance to Port Neville, we had tacked 25 times. I was very, very tired. This 12 NM trip had ballooned into 22 NM. The government dock was empty, the wind pushed us in a bit too aggressively onto it, our fenders let out a loud whine as we crushed them between Pino and the dock. | |

| The dock at Port Neville was old, abandoned, but still standing, it was mossy, some of the pillars were half-eaten. An old rusty refrigerator was lying on the dock, along with some disused fishing and crabbing gear. The mountains in this bay were bare, full of logging scars, robbed. The Port Neville government dock no longer had a wharfinger, and hadn't for a long time, but transient boaters continued to moor here. Anchoring in the bay was possible, but not ideal because of strong currents. This place used to host the longest running post office in British Columbia, the old building was still there, preserved as a historic site. Note: We later learned that the Tlowitsis First Nation would soon take ownership of the Port Neville wharf, and that there would be improvements done to the facility prior to the transfer. |

|

| Devine prepared pasta for lunch, while I started the woodstove. Spending a morning in the wind cooled us right down. After lunch, I sat by the stove, logbook in hand, thinking I would lie down and document the day's events, but the warmth of the stove put me to sleep. I was beat. Devine continued improvements on personal projects, to the sound of my snoring. I awoke to find that two other sailboats had joined us on the decrepit Port Neville dock. | |

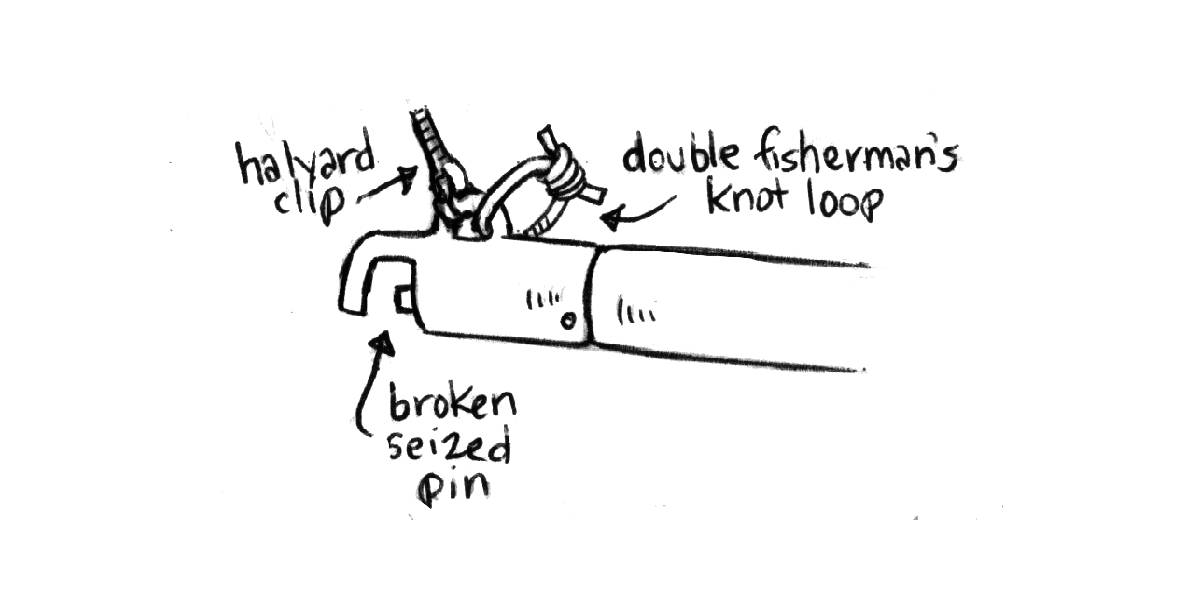

| We had poutine a-la-Pino for dinner, steamed potatoes(frying wasn't going to happen) with a homemade gravy on top — our potatoes were getting very old, this was a good way to use them up. I spent time fixing a fuel leak on Calcifer II. I realized that I had stripped the fuel bleeding screw while doing maintenance last spring, which resulted in a constant slow leak when the engine was running. We attempted a temporary fix, using fuel-resistant teflon tape(not ideal, but it's all we had). |

|

| Week 3 | |

| May 15th | Port Neville to Telegraph Cove At 0600 our two dock neighbors were already underway, we left shortly after. Today the wind was 15 kn out of the northwest, but we saw that Weather Canada had a gale warning out for Johnstone Strait tomorrow afternoon (30-40 kn northwest) At 0600 our two dock neighbors were already underway, we left shortly after. Today the wind was 15 kn out of the northwest, but we saw that Weather Canada had a gale warning out for Johnstone Strait tomorrow afternoon (30-40 kn northwest)Port Harvey and Boughey Bay would have been 2 good anchoring options to weather out the passing gale, but because it was still early in the day when we arrived at Havannah Channel(the channel leading to the two anchorages), we decided to push on. The downside of anchoring at either of the aforementioned anchorages was that both were further inland, adding extra miles to get there and to return. Aiming for Boughey Bay required us to sail backward for 4 NM — not a desirable prospect. |

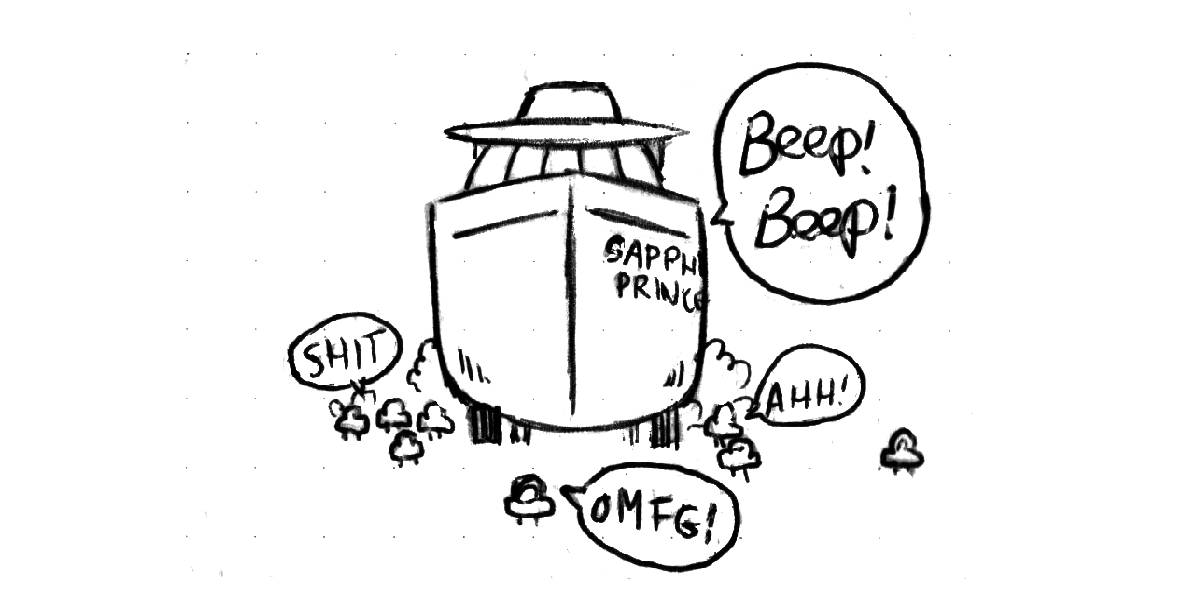

| A cruise ship hurried past us, its wakes transformed the sea around us into ocean waves, and its exhaust trail clung to the air long after it had gone. This was the first of many we would see on this trip. The wind left once we passed Havannah Channel, but the current added 2 kn to our speed. We put our engine to work. Peeking inside Calcifer II's chambers, it appeared that the fuel leak had stopped. Arriving at Port McNeill today would have been nice, but it was too much distance to cover in one day. We settled on stopping in Telegraph Cove, despite the fact that their facilites were designed to specifically accommodate trailerable boats, we were able to secure a spot. When we arrived the tide was very low, making the already very narrow entrance into the port appear even more restricted. Pino's fin keel allowed for quick turns, it was an asset in this particular port because of where our mooring spot was located. Near the entrance, we had to circle around an old piling to get to it — we think there used to be another finger here. The marina was empty, devoid of both boats and humans, business was not booming. |

|

On arrival, we searched for the marina office to pay for our moorage. The harbour front consisted of colorful stilted buildings, with antique hardware strewn across the walkways and boardwalk as decoration. We wandered into the wrong marina office. Despite it being a very small town, the workers at the desk had no idea where the office for Telegraph Cove Marina & RV Park was. "Really?" we thought, "you don't know the location of the office of the marina neighboring yours? The only other facility that you share this tiny harbor with?" On arrival, we searched for the marina office to pay for our moorage. The harbour front consisted of colorful stilted buildings, with antique hardware strewn across the walkways and boardwalk as decoration. We wandered into the wrong marina office. Despite it being a very small town, the workers at the desk had no idea where the office for Telegraph Cove Marina & RV Park was. "Really?" we thought, "you don't know the location of the office of the marina neighboring yours? The only other facility that you share this tiny harbor with?"We wandered around and eventually found the office ourselves. In the shoulder season the workers don't occupy the office building, we had to call them. The owner arrived in a 4x4, with a labrador friend riding in the back. He told us about some of his favorite places in Southeast Alaska. "I caught so much halibut up there!" he said. He sang the praises of fishing for a short while, we listened intently — we didn't have the heart to tell him we didn't eat fish. |

|

| We went to bed early. We thought of staying here for 2 nights due to the coming weather, but we figured we would have time to get to Port McNeill before the weather turned too sour. We were glad the weather was cooperating, but moving non-stop cost us much of our energy. At least, we would be allowed to sleep-in tomorrow because the current only turned in our favor at 1100. We preferred to do transits in the morning, but we couldn't ignore the strength of the current in these waters. The wind was supposed to blow 20 kn out of the northwest, increasing to 20-30 later in the afternoon. We wanted to stop in Port McNeill to replenish our stores of fresh foods, we were down to a few sprouted potatoes, 1/2 a daikon, a 3/4 head of cabbage, and some garlic cloves. We also wanted to buy some firewood for our stove, because the weather will continue to be wet and cold for a long, long time... |

|

| May 16th | Telegraph Cove to Port McNeill Rain, rain, and more rain, it looked like rain would accompany us to Port McNeill. The forecast hadn't changed. Crows kept landing in our cockpit, we watched them through the quarter berth window. "Hm, the weather is not good!" One of them said. We could hear another walking on the deck. Tick, tick, tick, followed by a sudden and loud "CA-CAW!" — code for, "Not good!" They were trying to warn us to stay where we were, but we had it in mind to leave at 1100 to get to Port McNeill, a short 10 NM sail away. From out spot, we could see that there was wind out there, our bow was facing the opening. Telegraph Cove was a safe place, shielded from the elements. We could observe the chaos from the safety of our little quiet nook, but we chose to leave. |

| We added 2 reefs in the mainsail. We knew it was going to be rough, but 10 NM was nothing. The wind was tame, but got stronger as we approached Cormorant Island(lying between Telegraph Cove and Port McNeill). The passage south of Cormorant Island appeared narrow, difficult to tack through, so we decided to sail around the top. It was very rough up there. The wind increased yet again, we had many waves leaping up on deck, our faces were quickly encrusted with salt and various sea things. Tacking in heavy weather is much more demanding. After tacking, I could never reel in the jib sheet back fast enough, the sail caught the wind too quickly, Devine had to point Pino's bow into the wind longer so I could manage it. |

|

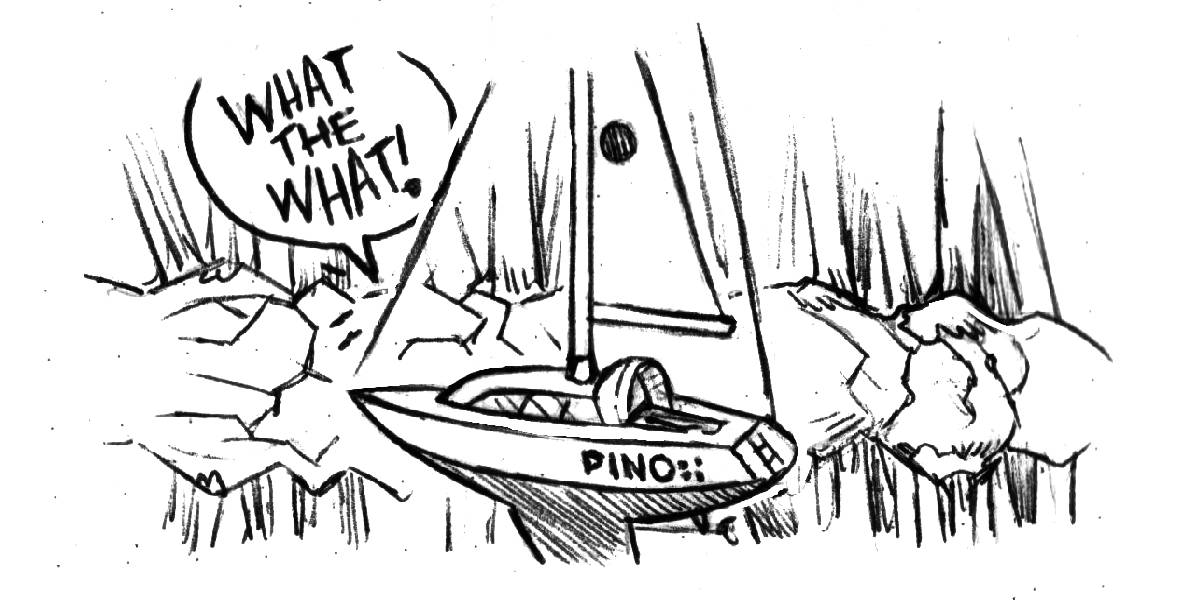

| By the time we sailed past Cormorant Island, the water was covered in white caps. We battled 20-25 kn out of the northwest, on the nose. It was a very harrowing ride, our path encumbered by both still and moving threats, shoals, reefs, the ferry to Sointula and Alert Bay. The ferry had time to pass twice, we had to tack to avoid it. We imagined the passengers aboard, watching our progress, seeing the sea as it was, thinking that we must really love sailing. Meanwhile, both of us wished we had listened to the crows and spent the night in Telegraph Cove, our cosy, calm nook. We had not considered wind against tide when we left the dock today, we're not sure why we didn't. "We are such fools," I thought. Our rain jackets were covered with salt, our faces were stiff, hardened by weather, the ride felt unending, like we'd been at sea for years. We assumed that the ledge north of Port McNeill would shield us from this wind, it didn't. Pino's headsail is on a roller furler, in heavy weather, if we roll in the jib too tight it won't roll all the way, and if we roll it in too loose, or crooked, the wind will find a way in and cause part of the sail to balloon out while partially furled — this last bit happened to us today. While I was in the cabin on the radio trying to secure us a slip, the wind saw an opportunity to sneak into the loose bit of sail. "Oh shit!" I heard Devine say. We were very near the marina docks at the time, a terrible place for that kind of thing to happen. The wind pumped air into the top part of the furled sail, ballooning it out, the strong winds then caused the bulge in the sail to flail violently, shaking the entire rig in a very disconcerting way. At that point unfurling the sail was impossible, the only way out of this mess was to do a full 360-degree turn with the boat to unroll the balloon in the sail, only then could we unfurl the sail again to secure it(this wasn't the first time since has happened to us). The jib was well-secured after that, we made sure of it. All of this happened 10 m (33 ft) away from the dock, it is not fun to have an audience when things go wrong. |

|

| The only available spot in the harbour that day was at the municipal marina, the one most exposed to wind waves, laying outside the protection of the breakwater. The other marina was full up. "Blustery wave pool it is!" we said, as the wind brought us onto the dock. We added our line snubbers to the bow and stern lines to try and cushion the violent motion. The fenders were screaming with every wave, there was white foam everywhere, a storm was brewing in the gap between Pino and G dock. We had come to Port McNeil to re-supply, but also to relax, this wasn't relaxing. When inside the cabin, it felt like being at sea. Being at anchor might have been a better choice, but moving was not possible now, Pino was pinned to the dock by wind and waves. We had made a lot of bad decisions today. After paying our moorage, Devine desperately wanted time off the boat, we went for a walk in town to the grocery store. We bought a baguette, cucumbers and carrots. "Fuck it," I said, "let's buy some pre-made hummus." We never buy pre-made hummus, we always make our own, but today we were tired and hungry. I then saw the price of a small tub of hummus, "we... are making our own hummus!" |

|

| When we arrived back to the chaotic mess that was our home, I went to work quick-cooking some chickpeas, I prefer to soak them overnight, but today we had decided on it late. I parboiled some dry chickpeas for 10 minutes, covered the pot, let them rest for an hour, then cooked them in the pressure cooker. For a moment, I wasn't sure homemade hummus was going to happen, because somehow I had lost the pressure cooker's little rubber vent plug, without it the cooker wouldn't hold its pressure. Luckily, I had kept the old one as a spare! I had replaced both the plug and the seal earlier this year, the seal was too worn to keep, but the plug was fine. We ate our hummus, doing our best to ignore the weather outside. A good baguette helped to soak up our worries. |

|

| May 17th | Port McNeill The boat quit being a bouncy castle sometime in the night. Come morning, the wind and waves having diminished, we moved Pino to a better, unoccupied spot. The harbourmaster had told us that we could move to that slip when the weather abated. Once at our new protected spot, we prepared some pancakes and coffee. Today was a day of rest! The boat quit being a bouncy castle sometime in the night. Come morning, the wind and waves having diminished, we moved Pino to a better, unoccupied spot. The harbourmaster had told us that we could move to that slip when the weather abated. Once at our new protected spot, we prepared some pancakes and coffee. Today was a day of rest! |

| After lunch, having just learned what a burl was, we went to seek out the world's largest burl, displayed nearby in Port McNeill. It was cut off a 552-year old Sitka Spruce. Unfortunately, the burl had lost some of its former majesty, it was now half-charred, laying in the gravel and bound with security tape. Last year, 2 teenagers had set fire to it, the burl wasn't consumed entirely by the flames, but it bore the injuries of that event. Despite the event, the crispy burl continues to draw in tourists. Walking on, we went to the hardware store to pick up a small maul and some fire wood. Up until now, our good friends Rik & Kay had been giving us starter for our stove, since they too had a wood stove and that ours wasn't terribly demanding. Now, it was time for us to chop our own! |

|

We bought a few logs, found a nice small(but heavy) maul, and went to work splitting the wood on the marina docks. Devine would hit the back of the maul with a hammer to help it along, then break off thin pieces, which I would then cut in half lengthwise with a hacksaw(so it could fit inside our tiny firebox). We knew we couldn't carry enough wood to keep the stove running constantly, but it was useful to warm our space on cold mornings and late evenings. We filled Pino's aft locker with wood, storing the rest in bags in the starboard side cockpit locker. We bought a few logs, found a nice small(but heavy) maul, and went to work splitting the wood on the marina docks. Devine would hit the back of the maul with a hammer to help it along, then break off thin pieces, which I would then cut in half lengthwise with a hacksaw(so it could fit inside our tiny firebox). We knew we couldn't carry enough wood to keep the stove running constantly, but it was useful to warm our space on cold mornings and late evenings. We filled Pino's aft locker with wood, storing the rest in bags in the starboard side cockpit locker.We finished splitting the wood just as the rain started. The rain revealed a leak on one of the starboard side chainplates. When the deck dries out, we will fix the leak. |

|

| We met Viktor and Caroline on their Cheoy Lee sailboat Moonshine today, they told us they wanted to go up as far as Prince Rupert. They planned to cross Queen Charlotte Strait on Monday, we had our eye on that same window. Having one extra day to relax was nice, my entire body hurt. Sailing in big weather left us with bruises, my left side and knee hurt, and because of all the sawing my back now complained too. Devine also had a few aches. "My arms are like jelly," they said, after spending an afternoon splitting wood. Yesterday, Devine handled the rough sail and the jib ordeal very well. They responded quickly, and so effectively that the jib problem was soon solved. At times, I freeze up, waiting for death to come. I can handle difficult situations well most times too, but if my senses are overloaded, I get overwhelmed. I am so glad to have Devine aboard, everyone needs a Devine. |

|

| May 18th | Port McNeill Ahh—to sleep in! What a luxury! Devine resumed work on implementing Paradise in Modal this morning, while I updated the cruising notes on our wiki. There was a lot to say about the places we'd been so far, it is less overwhelming to document if I update it as we go. |

| After lunch, our plan was to top off our fuel. Moving the boat to fill 2 bins seemed silly, so we called North Island Marina to find out if we could walk onto the fuel dock — the fuel dock was behind a locked gate, most people don't walk onto a fuel dock, they bring their boats. The marina was kind enough to give us an access code. I fixed the leak in the chainplate, adding more butyl tape to seal the deck. |

|

| Later that day, we spent time with Viktor and Caroline. We will both cross Queen Charlotte Strait on the 20th, the only calm wind day since May 16th. During our conversation, Devine continued to spread the joys of sprouting legumes, Caroline seemed very enthusiastic about the process. | |

| We prepared sushi rolls for dinner, with avocado, cucumber, carrots and tofu. We don't always eat well in the summer because we lack fresh ingredients, but this year we left Victoria with 15 jars of lacto-fermented vegetables. This summer, we also bought small quantities of beet and kale powder. Fresh beets and kale don't last, but the powders, if kept dry, last a long while. We like to add beet powder to chili, hummus and pasta sauces. Kale powder is bitter, more difficult to mix into meals, but we try to add it as often as possible. | |

| These days, by 2000 we are in bed, not sleeping, but doing whatever we'd be doing normally... but in the bed. May mornings and evenings were still cold, both of us tucked into bed was a great way to keep warm while saving on wood. We heat our bodies first, with clothes and blankets, if that wasn't enough, we fired up the wood stove. At around 2130, I read aloud to Devine, either until they fell asleep, or until my jaw got too sore. |

|

| May 19th | Port McNeill The wind has not stopped roaring ever since we arrived, the afternoon winds were especially ferocious. We didn't have any tasks planned for today, we just wanted to buy more food, fill the water tank, and maybe study anchoring options for tomorrow. This was our 4th day in Port McNeill. We enjoyed our time here, but now we were eager for some quieter weather that would allow us to move on. We'll get up at 0430 tomorrow to catch the last of the ebb out of here, then we'll see how far we can get. We will still have to contend with currents in these waters, we're looking forward to not having to plan around that (a note from the future: oh Rek, you sweet summer child... from that point on the current planning never stopped). Planning around gales wasn't fun either, but that's what we get for sailing in this area in the shoulder season. We have to make progress when the monster's eye isn't fixed on us. |

| This was our last dock day for a long while. We will go to bed early, and hopefully the ocean will treat us well tomorrow. | |

| May 20th | Port McNeill to Millbrook Cove Up at 0430, gone 20 minutes later. It was dark, but the harbor was well-lit. Caroline & Viktor waved us off, they were moments from leaving too. The current would be with us until 0730, we had to make as much progress as possible before it turned to full flood. |

We left the marina first, but after rounding the Pulteney Point Lighthouse, boats started catching up to us, their cruising speed permitted them to leave a little later, they too were eager to move on the one day that a gale warning wasn't in effect in Queen Charlotte Strait. Our sails were up, but Calcifer II was doing most of the work. A light wind added to our speed, but it was slowly dying off. Moonshine was behind us, they overtook us, and quickly disappeared into the faraway haze. They took the middle route, while we chose to head towards the north shore. We knew the current would turn once we got there, if it hindered our progress too much we would backtrack to Blunden Harbour, if it didn't we would go to Allison Harbour, or Miles Inlet. We left the marina first, but after rounding the Pulteney Point Lighthouse, boats started catching up to us, their cruising speed permitted them to leave a little later, they too were eager to move on the one day that a gale warning wasn't in effect in Queen Charlotte Strait. Our sails were up, but Calcifer II was doing most of the work. A light wind added to our speed, but it was slowly dying off. Moonshine was behind us, they overtook us, and quickly disappeared into the faraway haze. They took the middle route, while we chose to head towards the north shore. We knew the current would turn once we got there, if it hindered our progress too much we would backtrack to Blunden Harbour, if it didn't we would go to Allison Harbour, or Miles Inlet.The wind left us after we passed Port Hardy, we knew this would happen, but Pino and the rabbits pushed on. |

|

| The day was mostly grey, but a visit by a humpback whale illuminated the scenery. They swam alongside us for while, showing us their fluke before diving deep. The current did slow us down, but we were still going at 3 kn which allowed us to put a cross on stopping at Blunden Harbour. We put a cross on many more anchorages, because when we arrived at Allison Harbour we decided to push on. |

|

| Devine is really, really terrible at gauging how far things are. "So, where's Cape Caution?" I would ask, staring ahead at some distant mountains. Devine, who had the chart plotter in view replied, "it's right after that hill there!" No, it was not right after that hill there, it was after many more hills there, and would take 3 hours to reach. "Is that Cape Caution?" Devine glanced at the chart again, "yes!" No, it was not Cape Caution, we couldn't actually see Cape Caution yet, it was in that moment a barely discernible, pale hill, lying 15 NM away. Really, I think Devine does this to give me a sense of progress, saying "it's so close!" when it was 25 NM away. | |

| Arriving at Miles Inlet, we did that thing again when we change our mind and sail further. "It's so calm today, we should go around Cape Caution," Devine suggested. We had planned for stops at 8 different ports, to give ourselves some options should conditions change, all located on different parts of each leg, guaranteeing us a safe harbour no matter what nature threw at us. "Yea, okay! Let's do it!" I said. Conditions around most capes are bad in heavy weather, especially when ocean waves hit shallow waters near shore. This was true for Cape Caution, the waters shoaled to 9-15 m (30-50 ft) near the cape. To make matters worse, Cape Caution was preceeded by another danger: Nakwakto Rapids — one of the fastest and most turbulent rapids in the world. When the channel is at peak ebb with an opposing wind, the contact between the two will generate very large waves in the north part of the strait. Today, there was no wind, the ocean waves were down, Slingby was flooding, a perfect day for rounding the cape, but it meant spending much more time on the water. |

|

We passed near Cape Caution, a fine thing to do when conditions permit it. The sea near the cape was like liquid metal, highly reflective, and smooth. |

|

| Hello ocean swells! The waves were very tame today, but in the absence of wind the long swells caused the boat to roll, which in turn, sparked a feud between my ears and inner ears... in short, I couldn't finish my lunch. We saw our first sea otter! We mistook it for a floating log, with 2 truncated branches, but when the driftwood uncrossed its legs and dove, then we knew. |

|

| We raced a fog bank to Millbrook Cove, Pino crossed the finish line first. We dropped our anchor in 8 m (26 ft) at exactly 1800, having crossed the whole length(55 NM) of Queen Charlotte Strait. Devine went to sleep as soon as we arrived, burritoed into our fluffiest and warmest eggplant-colored blanket. Moonshine was there, we had not expected to find them here, then again, we weren't supposed to go up this far either! We had made a lot of progress today, we were officially past the top end of Vancouver Island! |

|

| Later, we fired up the wood stove to rid our space of dampness. The rain started at 2000, the chainplate leak was now gone. We had pasta with garlic and chili flakes for dinner, while using the last of my laptop's battery to watch Hunt for the Wilderpeople. There was no cell reception here, but we could get the weather via VHF. |

|

| May 21st | Millbrook Cove La grasse matinée ce matin! We got up late, weary from yesterday's long day on the water. The wind was supposed to rise to 20-30 out of the northwest today, that was too much wind to beat into. We were in open waters, we would not make good windward progress in big seas. When heading out of Millbrook Cove tomorrow we will likely have to contend with some proper ocean swells, when coastal sailing, wave height is an important metric when choosing a day to go to sea. |

| By lunch time, the wind was blowing hard into the anchorage, sending us flying with every gust. It has been excessively windy ever since we left Victoria, yesterday was the only calm day. I tried to draw this morning, diving into my conworlds to briefly escape my tempestuous reality. Devine was having fun re-mixing a song. "Our house, in the middle of our... our house, in the middle of our... our ho-" The song repeats the same phrase non-stop, an appropriate theme song for a game like Paradise. |

|

The 20-30 kn forecast increased to 30-35 kn. Millbrook Cove, so calm yesterday, now a mess of wavelets and disheveled trees. Speaking of dishevelment, while browsing through a book about the sea creatures of the Pacific Northwest, Devine found my spirit animal: the disheveled sea mouse, a thing that lives on the ocean floor with unkempt hair. When struggling to solve a problem, I run my hands through my hair, throwing all of the strands in different directions. Welcome to the B.C. north coast, home to a never ending waltz of mean weather systems. Gales come in succession, leaving very little calm or moderate weather in between, because it amuses them to see us sailors cower into our little coves and bays. Gales make a game of trying to dislodge our anchors. The wind can be real mean sometimes, but it is difficult to be mad at wind, wind is our main fuel. You are making it hard for us to love you today, dear wind... Welcome to the B.C. north coast, home to a never ending waltz of mean weather systems. Gales come in succession, leaving very little calm or moderate weather in between, because it amuses them to see us sailors cower into our little coves and bays. Gales make a game of trying to dislodge our anchors. The wind can be real mean sometimes, but it is difficult to be mad at wind, wind is our main fuel. You are making it hard for us to love you today, dear wind... |

|

| Week 4 | |

| May 22nd | Millbrook Cove to Fury Cove The wind abated sometimes during the night, or at least could no longer make it past the treeline enclosing our anchorage. The wind abated sometimes during the night, or at least could no longer make it past the treeline enclosing our anchorage.We woke to the sound of a horn, Caroline and Viktor were leaving. "Weather was crazy yesterday wasn't it?" Caroline shouted, "see you in Prince Rupert!" And, off they went. Their departure gave us the kick in the butt we needed to begin our own day of sailing. |

| The wind was still 15-25 out of the northwest, our goal was to make it to Fury Cove, it ought to have been a short sail. We had a pleasant downwind sail out of Millbrook Cove, but as soon as we rounded the point, it was time to tighten the sheets and to beat to weather. A lot of this coast is reef-strewn, the oceanside appears to have been devoured by termites and the rocks are the crumbs left behind. We spent a lot of time putting distance between us and these "crumbs", pointing into the open Pacific for a short time. "Let's go to Kodiak!" Devine joked, I wasn't amused, 15 NM already felt like an eternity. We don't have as much patience for long sails when sailing near shore, because it demands more out of us, we don't have the option of heaving-to for a whole day if we're exhausted. | |

| We tacked back towards the shore, then back to the ocean, then shore, ocean, shore etc. We tacked yet again, but only managed to sail right back to our starting point. The closer we got to Calvert Island, the less progress we made. Calvert Island was toying with the wind direction, sending us away, as if to say: "Go play elsewhere!" To gain a few miles, and to have a better angle to the wind, we cheated, woke Calcifer II, and made it closer to our anchorage on Penrose Island. We resumed sailing once at the mouth to Fitz Hugh Sound. We were making progress again, but both of us were starving by then, but we'd wait to arrive before preparing food. Neither of us had checked the time, we pulled into Fury Cove at 1600 — yep, we had been tacking for nearly 6 hours. 15 NM, short sail indeed. | |

| Fury Cove was well sheltered, with a white sand beach and a gap in the trees opening onto Fitz Hugh Sound. The sky was blue, it was warm too. I shed my wool shirt, fleece, and base layers. Devine joined me outside on deck, we were like lizards in search of a warm rock, cormorants looking to dry their waterlogged wings. We ate some jap chae, while watching The Martian. We finished reading the book yesterday, and now we wanted to watch the movie to compare. Kristen Wig playing Annie was an excellent casting choice. |

|

| May 23rd | Fury Cove to Codville Lagoon Time to leave paradise. Our cozy window overlooking Fitz Hugh Sound confirmed that the wind had switched to the south. South Winds! Finally! We raised Pino's wings while in the lee of an island, and sailed north with the wind at our backs. After days of beating to weather, sailing downwind was like floating on a cloud. |

We set up the whisker pole for a better downwind angle for the jib. Marvelous. Sailing downwind was magical, like being pushed and pulled at the same time. But the motion is clumsy, Pino bobs from left to right. The only way we've found to describe this awkward motion is to imagine someone playing the tuba(YouTube) over a cartoon. |

|