computing and sustainability

This is a blog post based on a transcript of a talk Devine gave at Strange Loop on September 22nd 2023. Watch the video version(YouTube). The slideshow presentation was made using Adelie.

I'd like to thank the Strange Loop organizers, Jack Rusher for the lemon and honey drink, and Josh Morrow for lending their computer for the presentation.

An Approach to Computing and Sustainability Inspired From Permaculture

I first heard of Strange Loop a few years ago, the talk that introduced me to the conference was Programming Should Eat Itself by Nada Amin. It was the first time that I saw a form of play, with code, that really resonated with me. A few years later, Amar Shah gave a talk called Point Free or Die, and then I knew that I had found a safe place where I could exchange ideas on esoteric programming.

I co-run a small design and research studio. We were originaly planning on making video games, but we ended up, due to various circumstances, exploring how modern technologies fail. We've been operating entirely from donated devices for 8 years now, it allowed us to explore how different devices break, and how we can repair them.

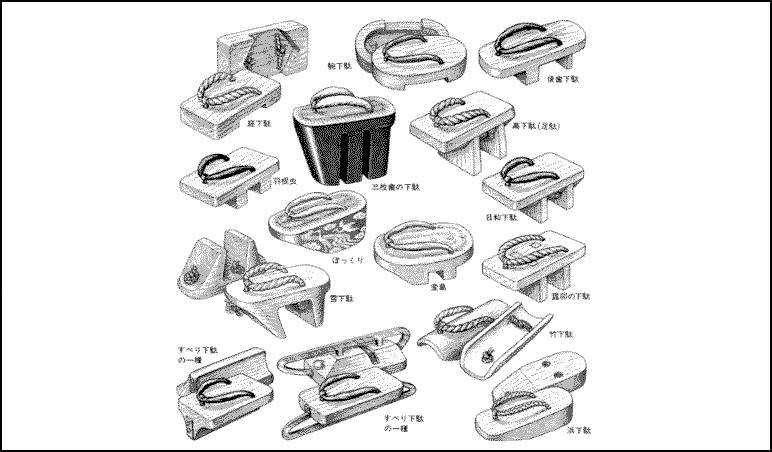

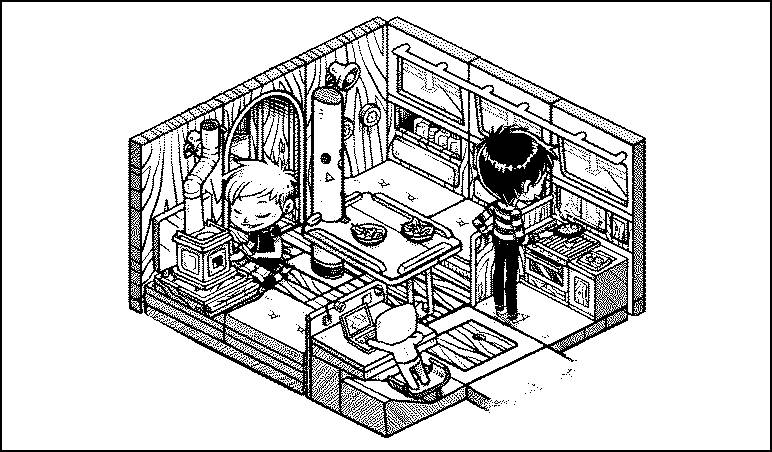

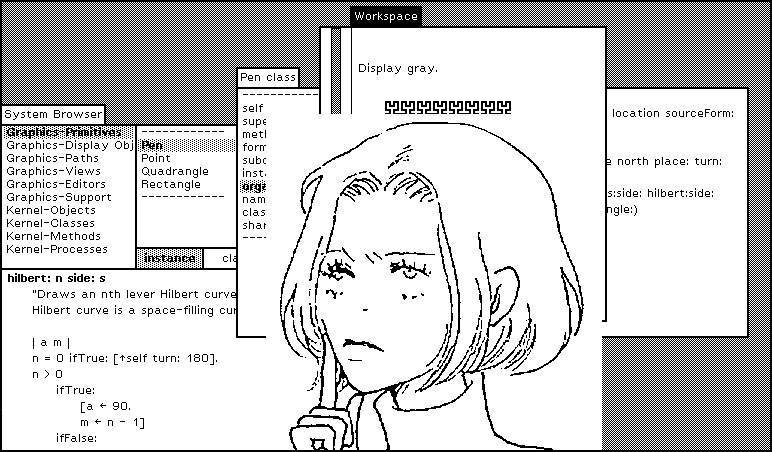

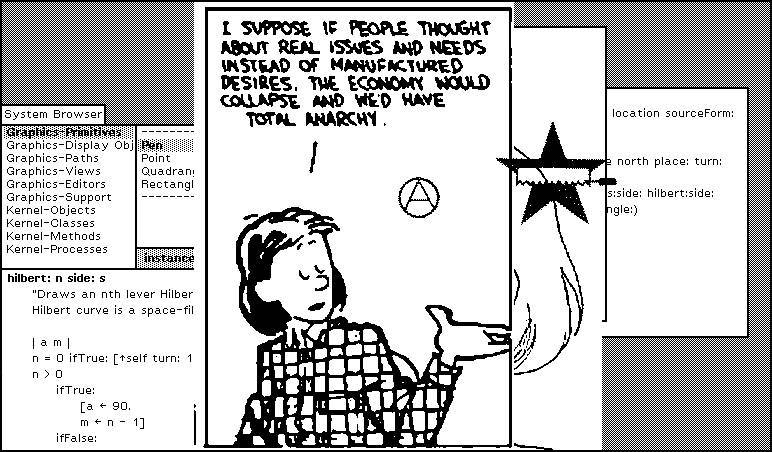

Some of these slides are Rek's drawings. Together we make books, tools, and games. We also document things that interest us with drawings. We like communicating dry topics with illustrations, to give people a way to connect with the material.

I am not an academic. I won't present any groundbreaking technology today, but I hope that you will all enjoy nonetheless.

In Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's book Wind, Sand and Stars, during a mail delivery, his plane crashes in the Sahara desert. There, he encounters a fox and notices that it only eats one berry in each bush. As he was starved, and that the bush was full of fruit, he couldn't understand why the fox would only take one. This talk is about that fox, who knows better than to eat every berry which could harm both the bush and other desert dwellers.

This talk is called An Approach to Computing and Sustainability Inspired From Permaculture. Sustainability is an awful word, that doesn't really mean much anymore. What I mean by this is being able to do something for a sustained amount of time. Permaculture is also an equally vague concept, when I say this, I mean that it is something that has a strengthening effect on the ecosystem.

I'm interested in computers as a way to do more than consume, as a tool of creation. For that reason I won't consider services, or apps. This talk is about open specs and on building knowledge to write your own software.

I'm going to present technologies, but I won't give you their names, because my goal is that you will develop your own systems. I'm not selling you on any one technology.

Nowadays, people shop for solutions, and given enough time, it creates a vacuum of knowledge. Solutions are a way of obfuscating knowledge. Knowledge disappears when you go from one solution to the next without taking the time to understand the whole arc of the story. If you go on StackOverflow, solutions are offered in a way that you don't have to think about the problem. "Just use library function X" is not portable, it doesn't equate knowledge.

There is this myth that we're building on the shoulders of giants, but when you're all the way up there on the giant's shoulders, it is really hard to steer it. We should be careful of those who make these bicycles-for-the-mind.

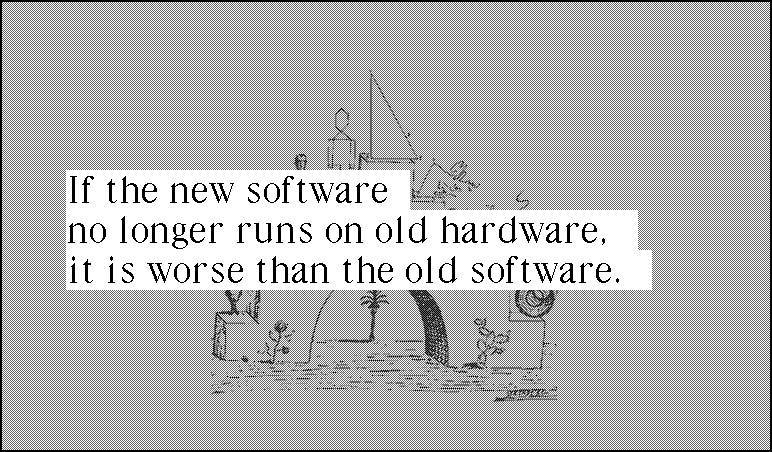

Complexity, simplicity, and sustainability, these are often repeated words at this conference, but the issue is that everyone has a different idea of what simplicity, or complexity is. Unlike the vague goal of designing a sustainable product, designing a product for disassembly is very clear. If I was to translate this to computing, saying that "I want to design software for disassembly," has this inherent property that could be seen as sustainable. This will be the limits of my usage of the word.

Kolmogorov was interested in defining complexity, and elegance. There are a few others like him that you might also be familiar with, but he inspired me to look into defining what is a complex program, what is a complex system. His definition of complexity in software is explained as the lowest number of instructions, rules, and exceptions needed to achieve a given state—note(my interpretation of his work).

I'm also interested in elegance. Elegance is another word for an index of complexity, or simplicity. Elegance is found in-between, and is defined in terms of limits. The best phrasing I've seen for elegance is "articulating the value of absence". To me, that was a very vivid explanation of this hazy concept.

One last concept I want to tie in before I move on, is the idea of sabotage. Sabotage is defined as "the withdrawal of efficiency". You may be familiar with the concept from the Luddites, and from those who clog machinery. The Luddites wanted technology to be deployed in ways that made work more humane, that gave workers more autonomy.

If we can agree that technology is only worthwhile as long as it benefits society, we must give people power over the technological system that rules their life, and the means to take them apart. It is extremely important for these systems to go beyond solutions, and include knowledge of the whole narrative that encompasses software. Software is not just an app that you download, it's also an definition of how to solve a problem.

If we put these three concepts together, if we're hoping to do something for any sustained period of time, we'll want to match our computing system to meet the complexity required as closely as possible. It's a very obvious thing to say, but people often use massive tools to solve really simple problems.

I spoke with someone earlier who's personal website was using all this crazy tech stack designed for enterprises' massive scale. Reducing our tools to address the core of the problem that we're trying to solve, is falling out of fashion. We're moving away from elegance when we give into these things.

I'd like to acknowledge that everyone's situation is different. Everyone has different limits. What I would like to advocate for is that people find these limits, and create solutions to address them directly. We can find limits that we all share with each other, simple things like the amount of water that you might need to survive.

As a metaphor we'll use tap water. Water at the turn of a tap feels limitless. If you have water tanks it's different, you can see how much is left. Knowing these limits allows you to plan. Many companies have made a whole business of hiding these limits, and it denies us the ability to plan properly.

Imagine that you live on a spaceship. The spaceship is 10 m(33 ft) long, with 360 l(80 gallons) tanks of water. The distance you can travel on your spaceship is dictated by the amount of water that you can carry between destinations. If you think that you'll run out of water, because you know the amount that you consume and how much you can store, you'll plan accordingly. Not knowing this would be critical to the success or failure of the passage.

My partner and I live on a sailboat, that made-up scenario of a spaceship is actually our situation. It's a very small vessel. We've been aboard for nine years now. It's a really interesting research lab, which allows us to see our the limits of our ecosystem, its byproducts, its waste.

To give you an idea, we have 4x6V batteries aboard, and 190 W of solar, those are hard limits. Your intuition may be to install larger capacity water tanks, or to put more solar, but extending these limits always comes at a cost. On a sailboat the cost is immediate. Adding more solar panels means you have more windage, more chance of getting knocked down. If you have more water tankage, you move slower, making it harder to get away from bad weather.

You have to make trade-offs. Overtime we found a balance in all this, and it leaves very little space for computation.

In Japan, they have mascots for everything, they even have a preparedness rhino named Bosai(Bosai is a Japanese term referring to countermeasures against natural disasters at all stages, from prevention and mitigation to post-disaster management and reconstruction).

I think about Bosai all the time. Because Japan experiences a lot of natural disasters, it is common for people to keep a ditch bag containing essentials like water, food, a toilet paper roll, and medical supplies next to the door. This is a sort of resilience that is really interesting.

I'm not saying that everyone should go on the ocean, that our situation scales, or that everyone would be happy in these situations, but I don't think that what we learn is uniquely tailored to sailors. There's a lot of portable knowledge in what we do that I would love to see applied elsewhere. You can adapt to the limits of your own ecosystem, whether you live off-grid, in an RV, if you're mobile, or if you have limited internet connectivity.

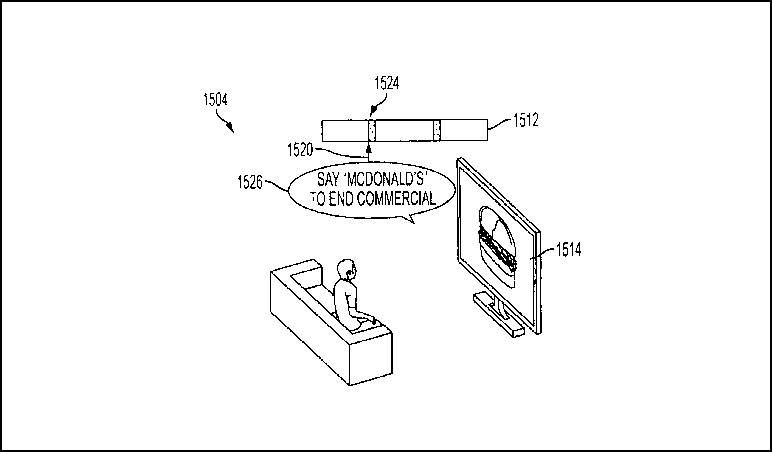

Nowadays people are expected to be online 24/7, but when away from city centers the internet is actually shit(or expensive). Sailing around the Pacific, we noticed that people expect to have internet all the time. There are many communities who are left behind when we design systems that expect the fastest computer all the time.

When we moved aboard our boat, we tried to replicate the lifestyle we had on land. We were doing iOS development, 3D games, and all that sort of stuff, it quickly fell apart because the systems that we were using would eat through our batteries. We couldn't sustain the practice of computation, enough that it got us wondering if maybe computers were incompatible with being nomads. We considered doing something else, but we rather like this field of computation that we have, it's hard to let it go, and so we tried to see if we could reconcile the two in some way.

In our research what we found was that what worked before still exists, it's still out there. We changed the ecosystems that we were targeting. A lot of the software that people used before we could emulate, we could encapsulate, we could still use them even though the modern world had moved on. Using Slack on the boat was not going to work, but IRC was still around and working. It was like this for everything.

We started to look into old systems, for things we could repurpose. We walked back the history of computation to find where we could go.

One thing we noticed is that a lot of this history of computation was forgotten. There are no computation history classes in school. You can't expect people to always do the work of digging the ancestral past to learn how we got where we are now, but failing to do so creates myths. A lot of people think that ideas that died went away because they were bad, but it's almost never the case. When you start looking into these systems, it's always a social dynamic, or politics that made it so people forgot.

Emulation

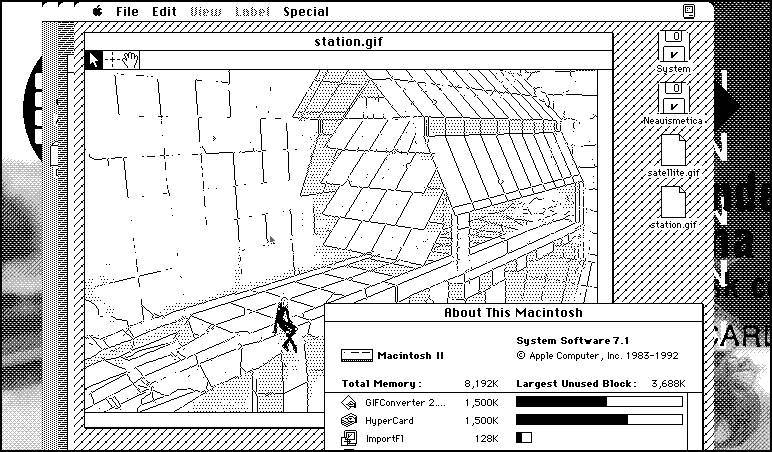

When you go through this process, you end up doing all sorts of different emulations of systems. I noticed that even though the systems were emulated, they ran faster and had better battery usage than modern software that were native.

I could draw in Hypercard for longer than I could draw in Gimp.

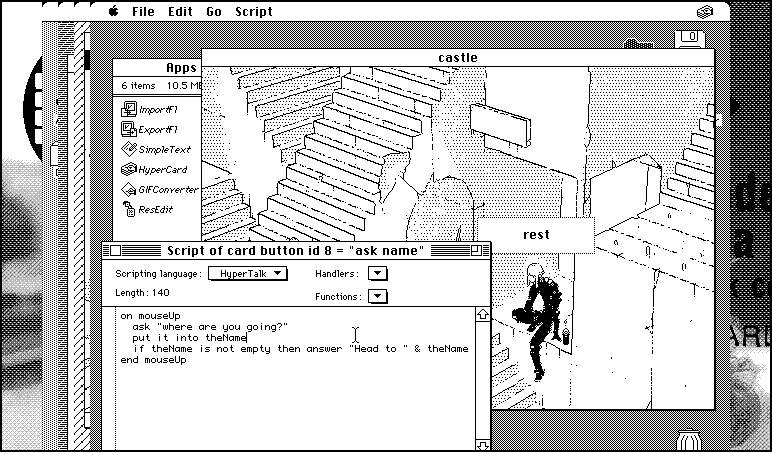

That changed how I was looking at this. You can do so much less in Hypercard, but maybe I could adapt the work that I do to fit within the constraints of these systems, that are more compatible with our life on the boat.

If you go through this legwork, you might even find that you'll want to make yourself at home in these systems.

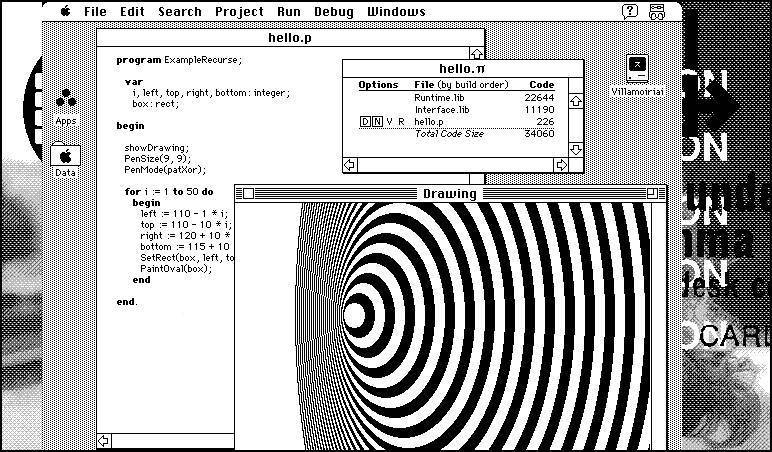

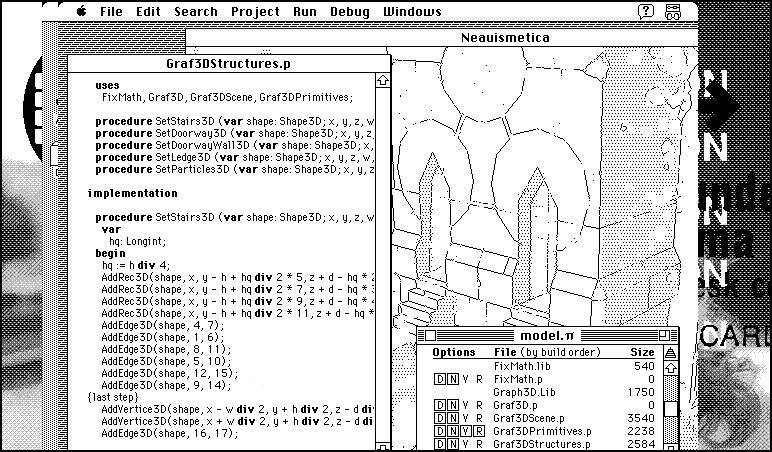

When I discovered THINK Pascal, I was blown away by how good it was. Almost everyone uses a monospace font when they program. There was an era where people programmed with Acme, where proportional fonts were more common. Why? As I said before, as things fall in and out of use, the ones that stick aren't used because they're better, it's usually because of trends.

I've made these 3D engines in THINK Pascal. Looking back to my system that used a monospace font, I was like well, now I miss THINK Pascal.

I messed around with these systems and it completely changed the style of the work that we did. You can either scale up, get more batteries, more solar, faster computers, or you can scale down. In all, I found I was super satisfied drawing in black and white.

Preservation

Let's say we start to consider preservation. I found that preserving work living inside these systems was even easier than the other work that I did. We had hard drives full of these massive PSD files and Krita files. We had a hard time making sure that we'd be able to open these image files over a long period of time, this is not a problem when using systems that are frozen in time.

The NES is a frozen platform, it's not going to be patched, so you can be certain that it'll keep running. There are implementations of emulators for it everywhere, so you can be sure that if you make something that runs on it, it will run forever.

Looking into these systems I stumbled onto others who were also interested in this topic, usually it's people who live in the woods that don't have reliable internet and that also feel like they've been left out.

There are entire communities of people who see this as an aesthetic drawing bounds on what they're allowed to use in their craft. And, others who want to prepare for when the infrastructure starts to crumble.

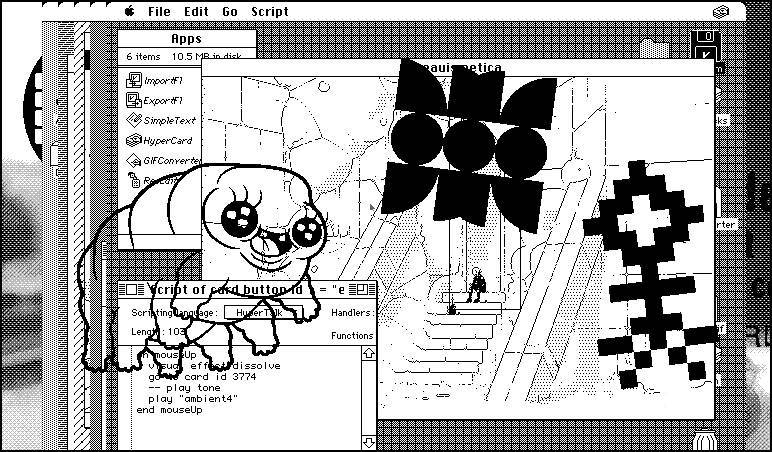

Working within these emulators completely changed the way I looked at computers.

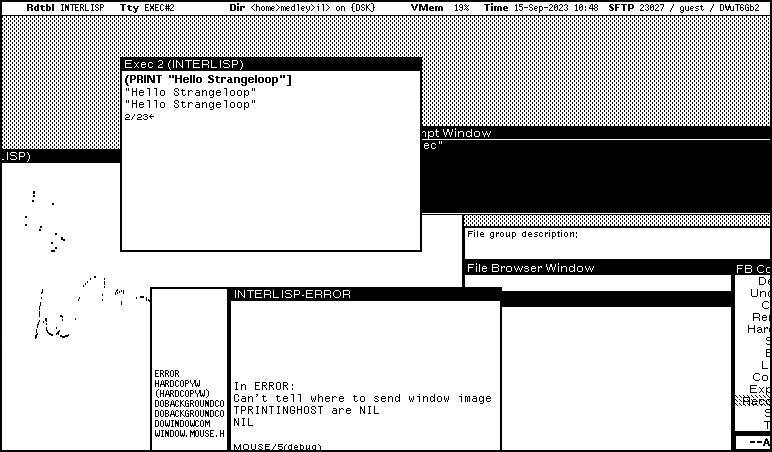

There was a trend in computation for a while where you didn't edit text files, you had a system that was image based in which you could navigate through the various states of the emulator. It would be a complete image—when I say image, I mean a key frame of state, the pixels on the screen, but it's also the whole runtime. If I give you this image, and you open it, you'll have the whole system at that time.

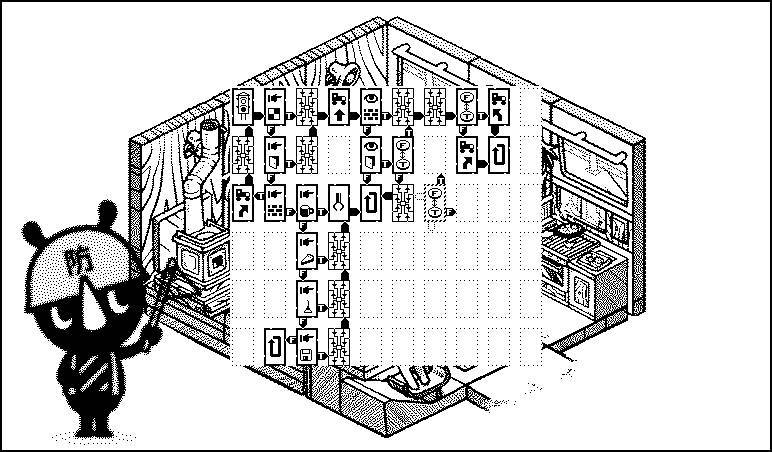

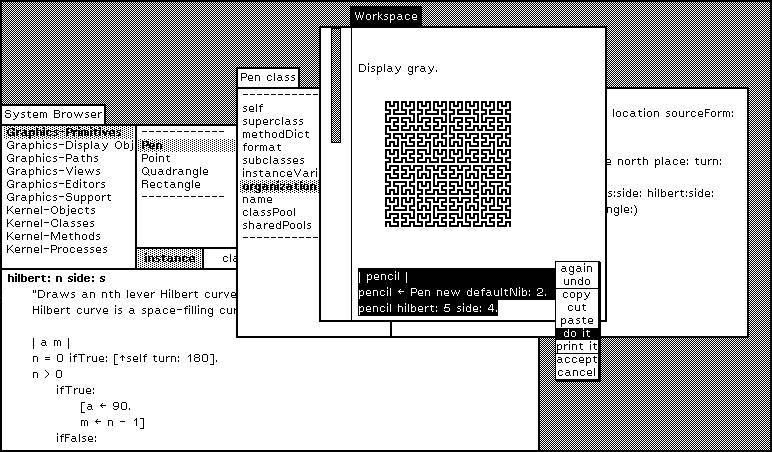

Being able to fork the states of how I was working, I thought was really cool. For a long time people have told me, "Oh, you should try Smalltalk." This is the Small Talk image for my computer two weeks ago.

You can still run these systems, they run amazingly well and are well documented. This is Smalltalk 80, it is 12 kb of code. In the Blue Book they say it takes "one staff year of work" to implement.

When talking about scale complexity, saying that something takes "one staff year of work" is an index of scale that is tangible. I wondered, if it's a year's worth of work to implement Smalltalk, then, what is a "one week computer", or a "one month computer."

I was curious to find a balance, an elegance that I could implement, but that would also permit my future self to re-implement. A "one year computer" I would probably hate myself for, but I could scale it down. Using Smalltalk I could see what I didn't need, and instead looked at what I did need, and designed a solution that fit my problem.

Looking into these various emulators, I began thinking about software preservation. I spent time in forums where people are into game longevity, they want to keep them playable in the future. That really resonated with me, because I spent years making iOS games that broke, Unity games that I can't open anymore.

Each time these ecosystems crumbled, I felt like a failure, like I was targeting a system that was so complex that me, myself, as an individual, I wouldn't be able to replicate. In that way, it wasn't really mine, I was making a product for someone else.

Software preservation became at the core of our practice.

I found a really disturbing statistic while writing this text, the Video Game History Foundation says that about 87% of all commercial games written prior to 2010 are now unavailable. This is a failure of our field. We're in a moment in time when people spend their adult life making one game, and 5 years later it is unplayable because of DRMs, system complexity. The preservation of these projects would advise people in the future of how we led our lives, what our interests were.

From my understanding, people who are looking into preservation don't seem to say that the market will want to solve this problem, so we can't rely on these ecosystems to do it for us.

As an aside, I want to mention that little PNG in the above slide that says: "because obsolescence sounds a bit scary." I had this PNG on my computer for a long time. It's on my website, I wanted to put it in the slides, but I couldn't remember where I got it from. I eventually did find the source, it is an illustration by Jenny Mitcham who works at the Digital Preservation Coalition. This image was embedded in a toot that no longer exists. I don't have a Twitter account, I had no way of getting to that toot and finding it. Apparently Twitter started deleting content, so even the people who should know better are using these platforms that bitrot faster than we can preserve them.

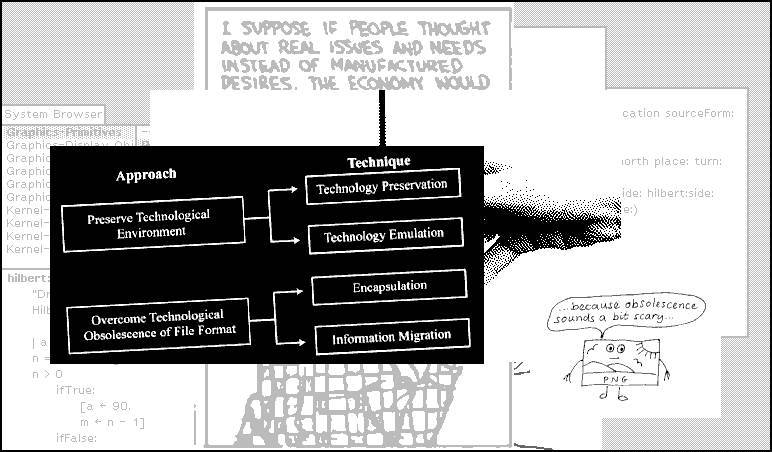

There's a few people who have developed strategies to work in digital preservation. They break it down in these four categories:

| Technique | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration | Periodically convert data to the next-generation formats | Data is instantly accessible | Copies degrade from generation to generation |

| Emulation | Mimicking the behavior of older hardware with software, tricking old programs into thinking they are running on their original platforms | Data does not need to be altered | Mimicking is seldom perfect; chains of emulators eventually break down |

| Encapsulation | Encase digital data in physical and software wrappers, showing future users how to reconstruct them | Details of interpreting data are never separated from the data themselves | Must build new wrappers for every new format and software release; works poorly for non textual data |

| Universal virtual computer | Archive paper copies of specifications for a simple, software-defined decoding machine; save all data in a format readable by the machine | Paper lasts for centuries; machine is not tied to specific hardware or software | Difficult to distill specifications into a brief paper document |

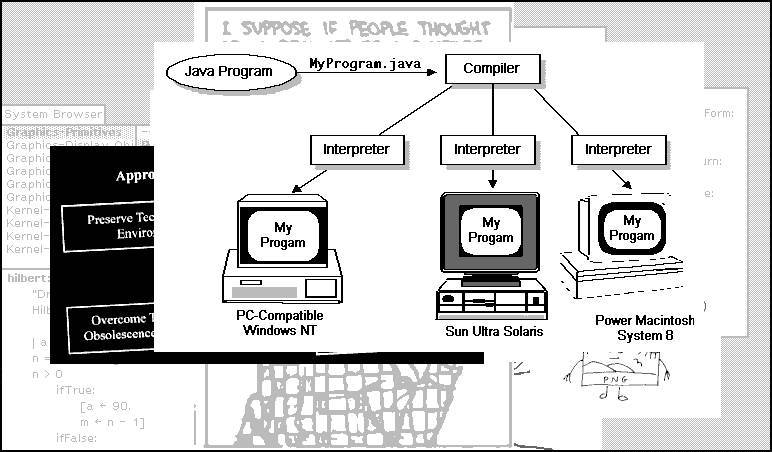

When going the UVM route, you do it from the start. You develop for an implementation target. It's a way of making a system that people could make new clients for. This, I really liked. I was told that this was the idea behind Java. I have never used Java, so I am not sure I've understood the feud between the different implementations, but I think it's a similar idea.

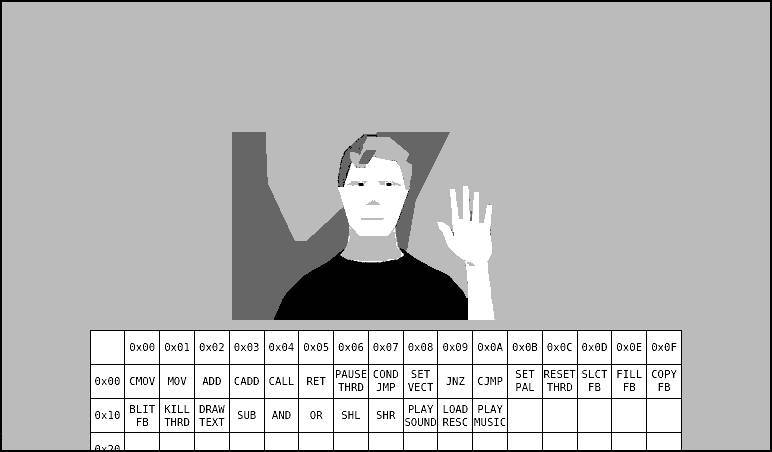

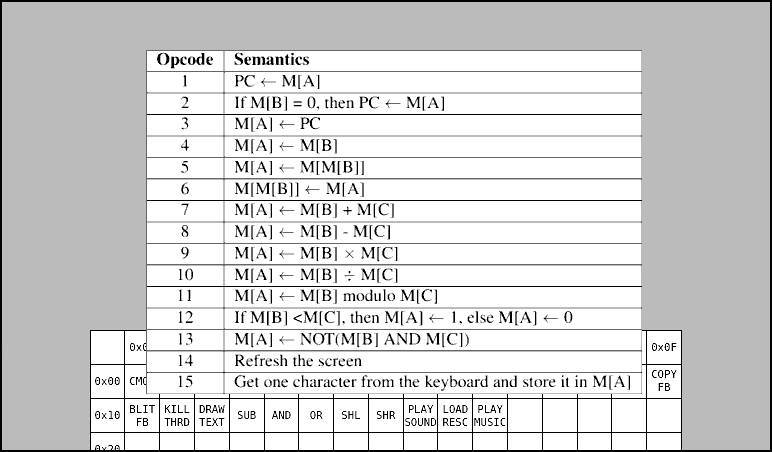

Another World is an older game that still lives because it was targeting a VM of 20 or so opcodes. This is the instruction set:

Implementing this means that you have a a client that runs Another World. It allowed the creator to make the game run on all sorts of systems, but also when he moved on to other things the spec was available so people reverse-engineered it. Eventually it became common knowledge and people could port it to modern systems like pico-8. It's going to take a while before this project disappears because people have a vested interest in writing little emulators because they're easy to write.

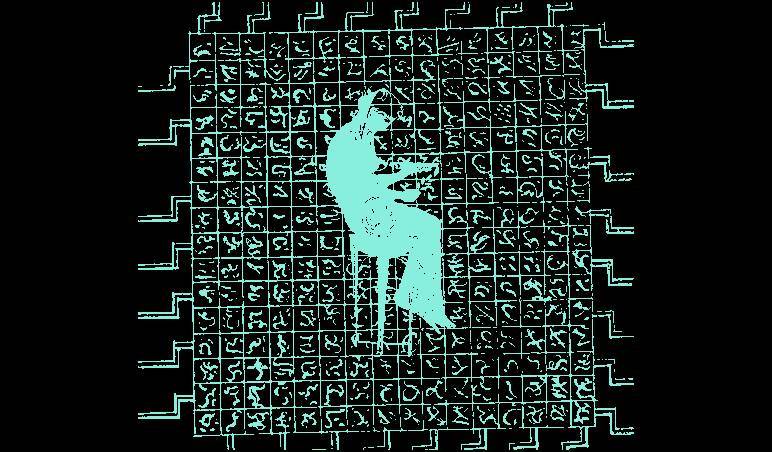

There's many other things like it. The above image is the instruction set for the Chifir computer, which was written by Long Tien Nguyen and Alan Kay. They were interested in these sorts of ideas too. They wrote a paper called The Cuneiform Tablets of Computation, in which they wrote how to make a super small VM to run Small Talk 726. They reduced it to these opcodes.

I don't think it was ever implemented, but when I saw it I thought, "Oh, it's like Another World, but for Small Talk." This is what I wanted, I'm never going to write another Unity game, and even beyond that, I want a way to encapsulate all the logic of a project and find its fundamental operations. Porting a project would mean translating the thin layer of emulation onto other systems.

I'd like to show you how we went about doing something like that.

I have a disclaimer, this is a feeble attempt at making a portability layer for our games. I should have led with this, but I am a terrible programmer. I am more of an illustrator and a musician, programming came really late to me. You're going to roll your eyes when you ever see the implementation. I'm not going to run you through the implementation, but I want you to know that I'm not vouching for this design specifically, it's as good as I could make it. What I'm trying to communicate is the idea behind it.

The way we scoped it was based on this one game that I wanted to port, called Oquonie. What is Oquonie? Imagine a VR project, something like Call of Duty, some 3D game... well, it's not that. It has been likened to Head Over Heels.

This was one cluster that we wanted to host. I imagined that if I hosted my website on this VM, which is a very different idea than hosting a game, it would stretch the spec to be a bit more versatile.

Another World had a VM that targeted specifically that game. I wanted something that would allow me to use one programming language to do multiple tasks. I do all sorts of different things, for instance I have a pretty intricate website. I wanted to make sure that I could port my website to this VM.

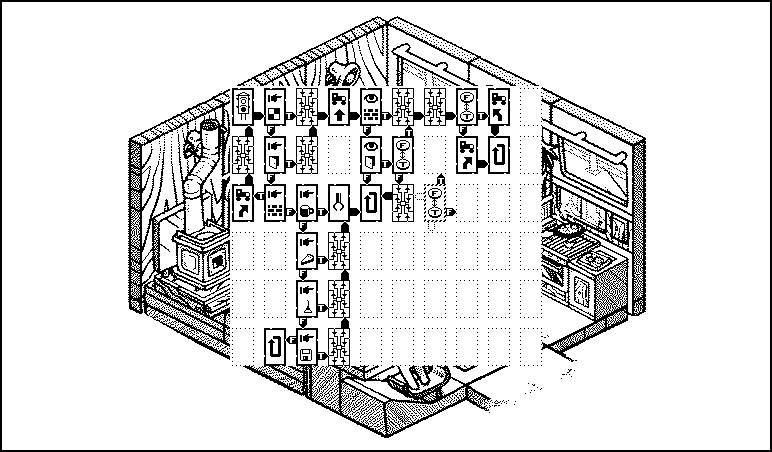

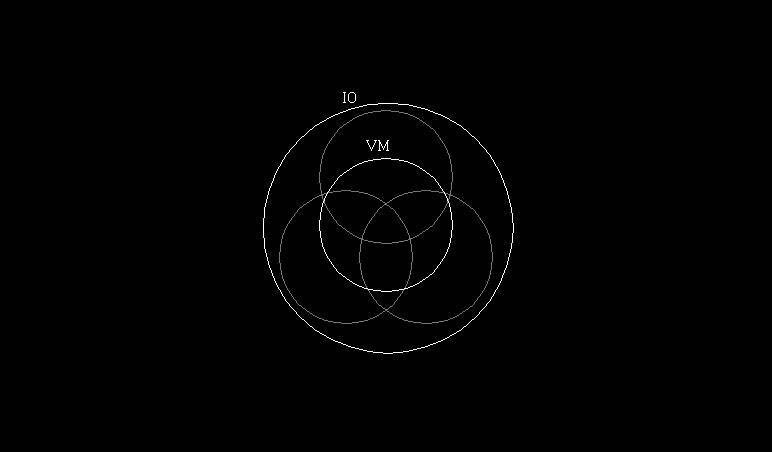

It's not only the game and its documentation that would end up on the website to be hosted on this VM, we also wanted the whole tool chain to be hosted on it. Right from the start the language was designed to be self-hosted. The assembler would be running on this, the text editor that I would be using to write the codes would be too hosted on this. There would be no moving in and out of different languages to do these projects, it would all be using the same virtual machine. The intersection between all these different things I wanted would be the VM.

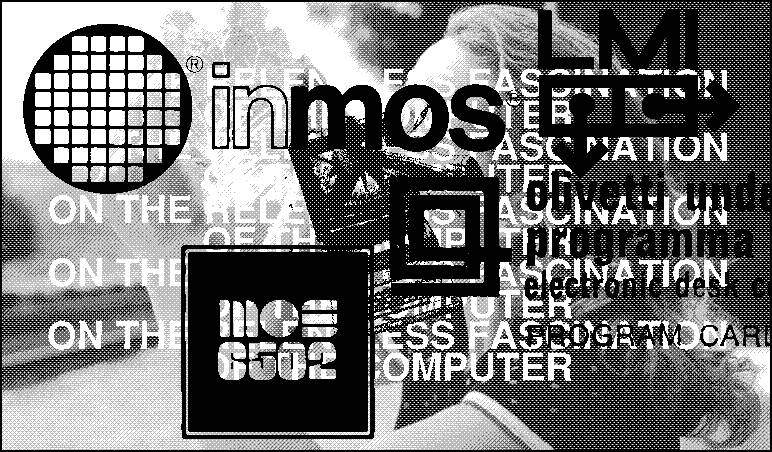

Finding opcodes, instruction sets, that would cover this was its core. Beyond this would be things that applications don't share with each other, that make up the computer system around it. The 6502 chip that runs the Nintendo doesn't do any IO, it doesn't draw pictures to the screen, it doesn't have a processing unit for graphics. This is part of the computing system around it, so this is the delimitation of the system that we chose.

I had written a bit of Assembly, I understood the concept. When all the games we'd made, all the computers we had didn't work on the boat anymore, we thought that we were going to make NES games instead. It's a great target, but there's no mouse, we wanted to expand from this. Making an NES game was my introduction to Assembly(see Donsol).

One of the first things I did was write an assembler for 6502, in itself. I thought I could live in that space, which feels more like operating power tools than trying to tell the computers what you want.

Assembly had one instruction per line, but I wanted to have something that was more like Forth, so it'd be more readable. I didn't see myself doing 6502 every day.

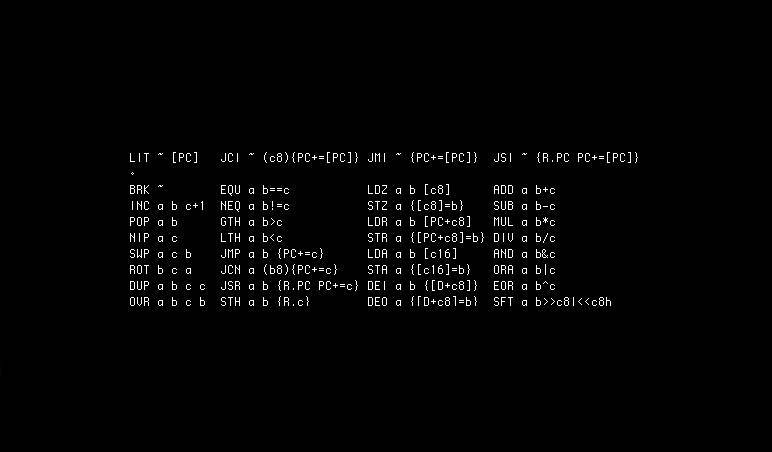

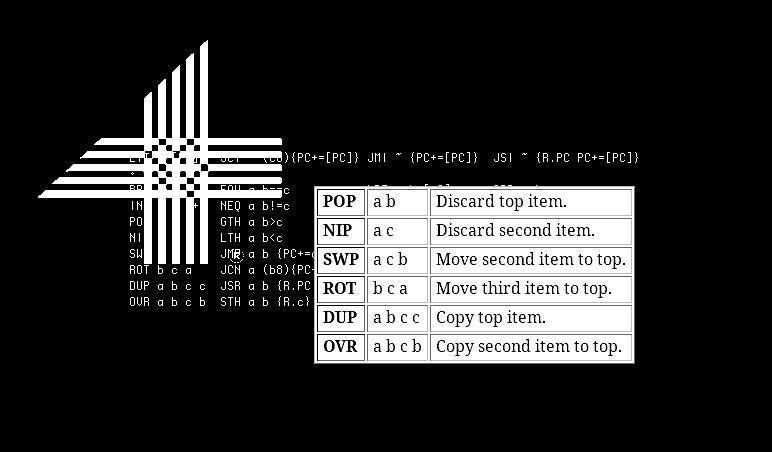

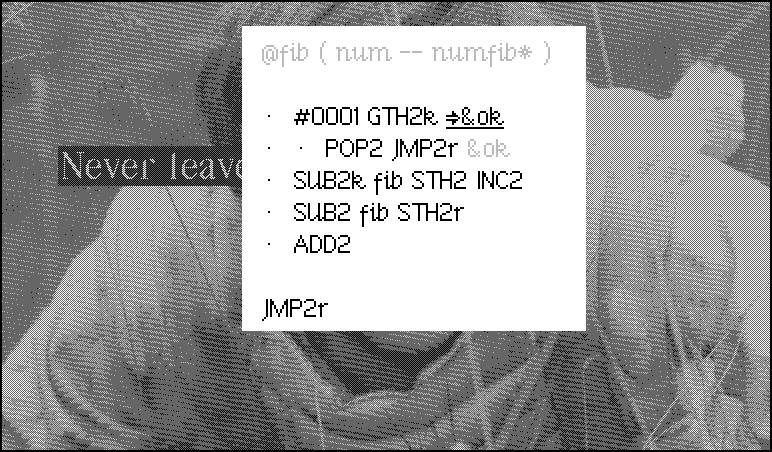

This is the instruction set that we ended up with, it's nothing special. We decided on 32 opcodes. It seemed like a nice balance, a good number that means that in a byte you have 5 bits per operation, and three bits for other things.

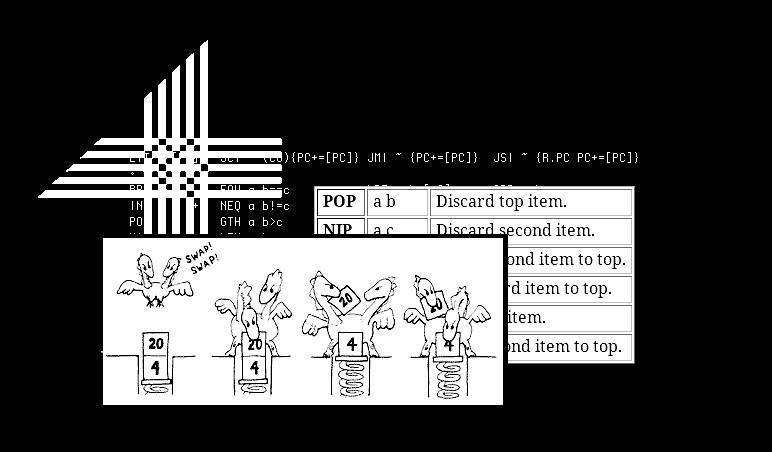

We decided on stack machines because when we were in that period of designing the VM, I discovered the program language Joy, and I resonated strongly with this way of programming. I realized that there's a ton of different schemes that you can use for doing this sort of system, but that was what seemed the most comfortable for us at the time.

We had written a little bit of Forth. Reading about Chuck Moore and his philosophy of design also resonated strongly with us.

If you're interested in that kind of stuff don't go straight for a stack machine, go check out what's out there first. There are tons of different ways of doing computation. Just recently, I learned about the Warren Abstract Machines, and was thinking, well, if only I had known about it at the time!

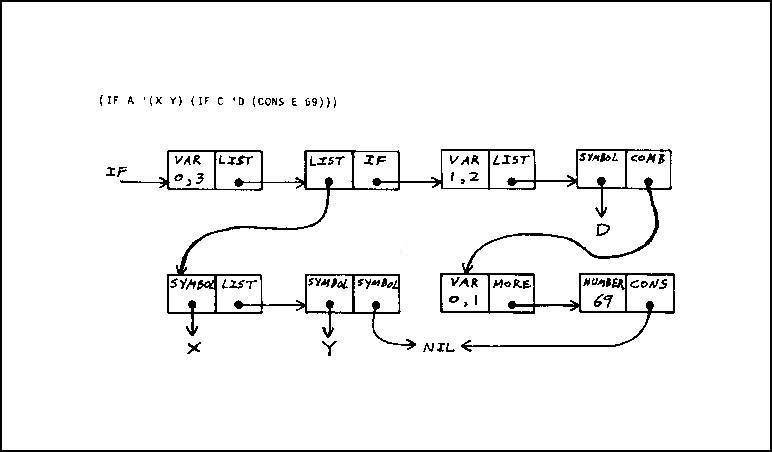

When looking into this kind of thing, the story starts to unravel really fast. Lisp machines are a forgotten art, there's also Tag machines, Interaction Nets, etc. There's a lot of different architectures that are super fun to use.

Joy, which I mentioned earlier, is a stack of cons cells. If you're going to rotate items in a stack everything is a con cell, so rotating many items means having changed three addresses. It's a pretty fast operation because it reduces the amount of data that needs to be changed. In a system, like the one that we chose, rotating 100 items is insane because it doesn't have this flexibility of cons.

Again, don't go directly for stack machines because I said so.

I decided that if we're going to program this thing, it has to have a language, and we didn't want to have a compiler. I designed the Assembly so I will be comfortable at that level, I didn't want to instantly have to abstract it. I decided on making a really comfy Assembly Language.

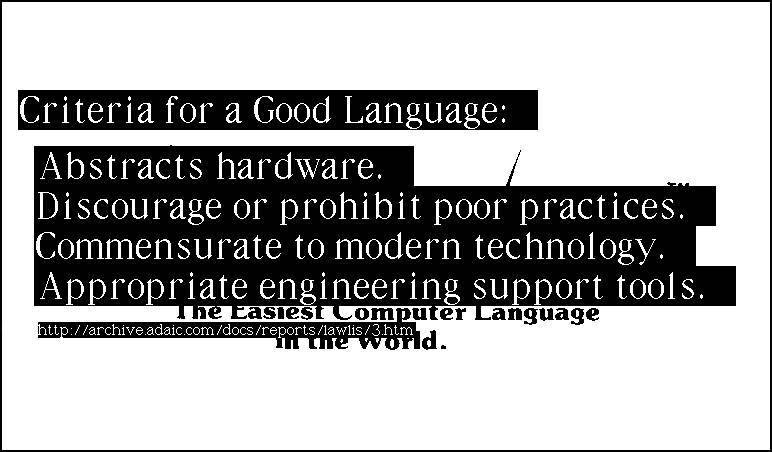

I went looking for the criteria for designing a good language, and I hated what I found. In short, the criteria advocates for obfuscating how things work, it states that the language only knows best, to go for a-la-mode aesthetics, and that you need a library and package manager, etc.

I was like, no, if that's what a good language is, then I'm going to make a bad language.

The language had to map one-for-one to bytecode, that restricted what I could do. Coming to Strange Loop I was afraid that my understanding of computation was subpar, and that people would see that I don't really know what I'm talking about. In the many Strange Loop talks that I watched I could see people had studied, and tried it, I'd only been doing this for two years and wasn't really sure I understood it fully, but one thing I noticed is that obsessing over programming languages is a distraction from computer science.

There's a big war going on at the top, people are trying to find the one thing that will work. In permacomputing, people are not looking for one solution, a good solution involves interactions between many things. The resilience of a garden, or a farm, is about interdependence. Companion planting is when two plants are grown near each other to benefit one of those plants, by fending off insects, for example.

What is ideal is an ecosystem of many solutions. Looking for a single one is a distraction from all this discourse. Coming into it from the outside, not having the words to find what I was looking for, I didn't have much to go on.

The rest of the talk is rather technical, and for those interested in the specifics of the language I designed, watch the rest of the video.

Thank you for reading.