sailing

- Reefing

- Navigation

- No schedules

- Ground tackle

- No windlass

- Communication

- Night sailing

- Seasickness

- Knots

- Safety gear

- Offshore sailing

- Insurance

During long passages, our daytime sailing occupations include: cooking, cleaning, doing fixes on the boat and brainstorming on future projects. We don't have a tight schedule for day watches, we hand the wheel to the other as we get tired.

At sea, I learned how little a person needs, not how much. — Robin Graham

reefing

Reefing is a way of reducing the area of a sail by folding one edge of the canvas in on itself. The loose material is folded, and lashed down to the boom with sail ties. Carrying a smaller sail is a safety precaution, reducing heeling and de-powering the sail to improve safety and stability in rough weather.

When sailing, if you can do the same speed with less sail, do it. As soon as you think of reefing down, do it. Should we reduce sails? Yes, always yes.

Shaking out a reef is easier than putting one in in high winds.

Before we start our night shifts, we usually reef the mainsail. A smaller sail will slow us down, but our main concern is safety. The rule is that if the wind rises enough to have us question whether we should reef or not, we do it. Another important rule, is to never reef at night. Everything is harder to do in the dark. We have done it before, with success, but the issue is that it means waking up your partner, robbing them of their precious sleep. Can't we reef a sail alone? Yes, we could, but that would break another rule: never wander on deck in the dark alone, even with a tether. Therefore, we plan to always do our last manoeuvres of the day while there is still some light out, at the cost of speed.

navigation

Our navigation rests upon an old refurbished Standard Horizon chartplotter, and Navionics (installed onto all of our mobile devices). Navionics's depth maps, compass, GPS, waypoints, community edits, and more, are all the features that we could ever wish for to get from A to B, over water. We use it along with a separate AIS tool for traffic. Navionics lists positions in degrees minutes seconds, or DMS for short.

The chartplotter was a donation from our friends on SY Dakota (they upgrade d theirs and gave us their old one). For now, it carries all of the maps for western canada.

We carry a sextant aboard, and both of us are learning to use it. Depending on GPS isn't ideal, and learning to navigate without it might save your life.

schedule

Sailing with a schedule is a recipe for disaster, too many things can happen on a boat and arriving on a precise date can be difficult. Making plans will make you do bad decisions, leaving in bad weather to make a meeting for instance, can be dangerous. Sail with the weather, not against it.

ground tackle

An offshore boat ought to house as many anchors as it can carry (Pino carries 2, we donated the third to a friend in 2022). The ideal anchor is one that can reset with ease if the wind changes direction.

Carrying multiple anchors is useful for kedging to get yourself out of a tricky spot (if you run aground), or to keep your boat off the dock in the event of contrary swell and wind. Kedging involves taking a dinghy out with a small anchor and line in the direction you want to move the boat. The anchor is dropped some distance away, and the person in the dinghy returns to the boat. Then, the sailor pulls the boat up to the anchor, a length of rope or so at a time. It is a slow, and difficult process but it works.

Some sailors argue that a bigger anchor is better, but the quality and shape of the anchor, as well as your scope makes all the difference. If you want to upsize, your bow roller may need replacing, and in the event of windlass breakage, heaving it up by hand could be next to impossible.

We carry many lengths of 3-strand nylon rode, to use for kedging, or for tying up stern lines when med-mooring in ports, or to carry and tie to a point ashore to keep from swinging in busy anchorages.

Read about anchoring etiquette.

communication

As a sailor, you must offer help to a boat in trouble. Radio communication is key, specific channels are used in every country for emergencies or information exchange. Every morning, sailors will tune in to a specific channel and listen to a morning net, a public radio exchange in which the weather and local events are announced, as well as boats seeking crew, or items that need to be sold or found. When the weather is foul, the local channels are very busy.

There is an unspoken understanding between long-distance sailors, an exchange of looks when foul weather is amidst. Every member of the sailing community knows the difficulties of life at sea, and is ready to lend a hand. We refer to each other by boat name, and like bird-watchers, we can identify rare breeds by sight. When transiting through world routes, we meet the same boats often, thus strengthening the connection. Talking to other sailors, and exchanging information is extremely valuable. You will make friendships for life.

On our 5-year cruise around the Pacific Ocean, we used a satellite phone.

radio

Onboard Pino we carry a fixed marine VHF radio, a handheld VHF and two transceiver Walkie Talkie two-way radios. VHF/UHF radio waves travel in straight lines (line-of-sight) generally cannot travel beyond the horizon. VHF (very high frequency) is the designation for the range of radio frequencies from 30 to 300 megahertz (MHz)

A marine VHF radio is an important and reliable for bidirectional voice communication both for ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore. In Canada, a Restricted Radiotelephone Operator Permit is required to transmit, it is unlawful to operate a ship station that is not licensed. The handheld marine VHF has the same functionalities as the fixed version, but is equipped with DSC(Digital Select Calling).

We sometimes use the two transceiver two-way radios to talk to each other from shore-to-shore, an Amateur Radio License is required to broadcast with this type of radio in Canada. A license ensures that new users are aware of the existing regulations and don't broadcast on reserved frequencies.

anchoring

When anchoring, use a scope of 1:3 when using all chain, or 1:4 if possible. More scope means less vertical strain on the anchor, and less chance of unsetting it. The longer scope is not always possible in tighter anchorages, which is why having a considerable length of chain will increase horizontal tension. A minimum of 15 m (50 ft) chain linked with at least 90 m (300 ft) of nylon rode is recommended. A nylon rode with a short length of chain requires a bigger scope, of 1:7.

Using a kellet near the chain/rope connection can help further increase horizontal tension.

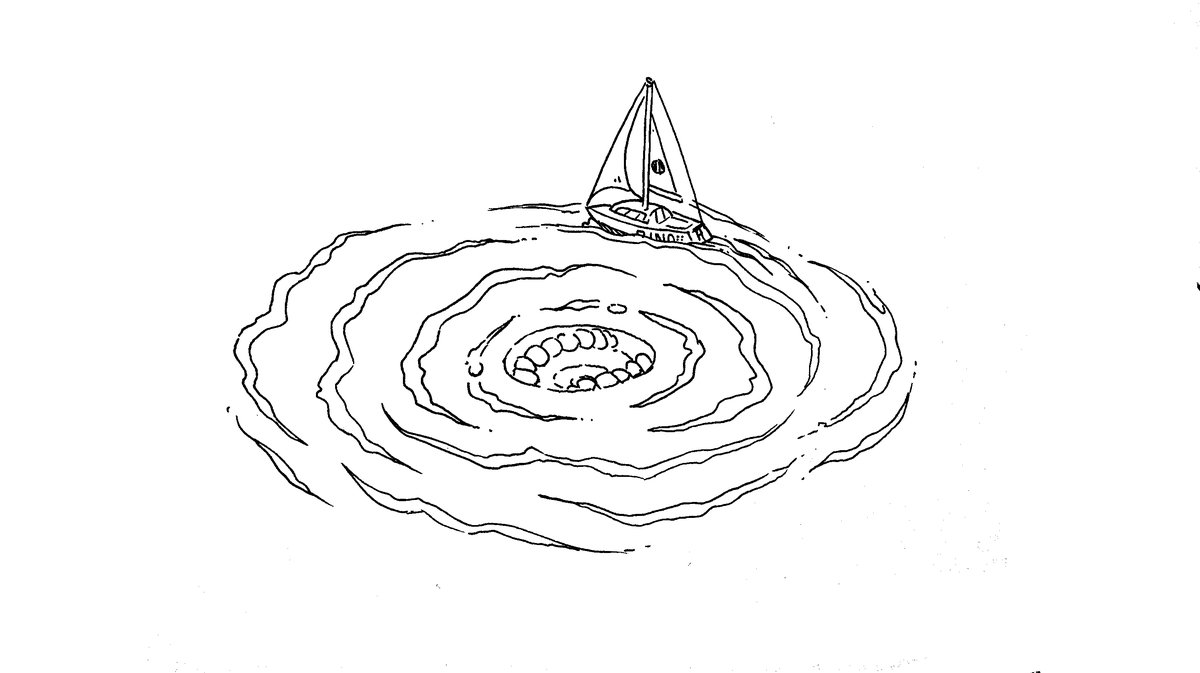

Don't anchor too close to your neighbor, especially if the neighboring boat is a motor boat, or much larger yacht. Boats orbit their anchors differently, especially lighter vessels. A lighter boat, with an all-nylon rode might "dance" around its anchor more and require more space.

When coming to anchor in a bay to find other boats already occupying it, observe how they are set up, and how far apart they are spaced. If unsure about the set up of a neighboring boat, ask, the last thing you want is to set your anchor too close to theirs. Some boats may have a stern anchor, which means they won't swing, and so if you are near, you must do the same or you will swing into them. Anchor behind other boats, or well in front if there is enough space, and try to stagger your spacing to one side or the other to avoid being directly off someone’s bow.

We prefer to anchor in waters no deeper than 11m, to make it easier to retrieve our anchor. We have found plenty of anchorages in the South Pacific in that depth range. Also, in many places in French Polynesia, The Marshall Islands, Fiji and Tonga, they recommend the use of mooring buoys to keep from damaging coral reefs on the seafloor.

Read about our anchoring setup.

no windlass

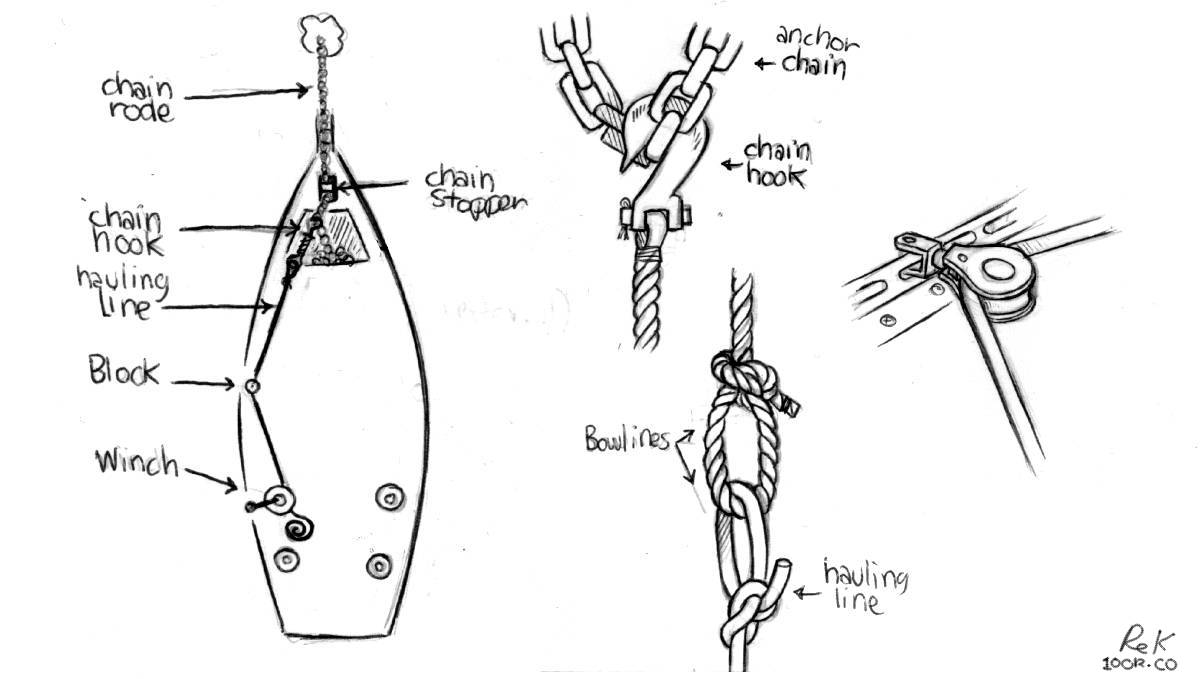

We haul the anchor up by hand most times, but when anchored in thick mud or deeper waters we like to lead a line back to the cockpit and to use the above method to haul up the anchor rode and anchor. It is easy to get hurt when there is a lot of mud on the fluke of the anchor.

We can only heave up a short length of chain at a time. When the chain hook is near the block amidships, we engage the chain stopper, loosen the line at the winch, then move the hook forward, then pull some more, and repeat.

night sailing

We used to be afraid of sailing at night, but now we look forward to it. It is the perfect time to think, to read, to listen to podcasts or music. It is easier to see ships in the dark than in the day, their locations are marked with lights.

On clear, moonless nights, we see a beautiful tapestry of lights overhead, a show that is becoming less observable in cities because of light pollution. Then, depending on where we are in the world, there is bio-luminescence in the water.

We prefer reefing the mainsail down at night, a smaller sail will slow us down, but our main concern is safety.

Whether night or day, we always wear tethers that we clip to a strong point in the cockpit. We have a pair of jacklines, flat nylon webbing that run the length of the deck that we clip onto if we need to go outside of the cockpit. At night, we never go out of the cockpit, even with a tether. A short tether is better than a long one. With a long tether you run the risk of falling too far overboard, making it difficult for the crew aboard to retrieve you.

Since we started sailing, we have stuck to the same pattern for night shifts. One sleeps between 1900 and 2100, then sails between 2100 and 2400, then goes back to sleep from 2400 until 0300, and then goes back to the tiller between 0300 and 0600. 3 hours on, and 3 hours off. Some sailors prefer longer shifts, doing 4-5 hours at a time. We prefer shorter shifts, because we get tired easy, and 3 hours, when tired, feels unending. If ever we need more sleep, we take short naps in the day.

seasickness

Here's a few of our tricks against seasickness.

- Don't drink alcohol or coffee the day before leaving.

- Eat before you're hungry.

- Rest before you're tired.

- Don't let yourself get cold.

- If everything else fails, take the helm.

knots

Terminology

Bend. A knot used to join two ropes.

Binding knot. A knot that constricts a line/object, with the ends joined or tucked under the turns of a knot.

Hitch. A knot that joins a rope to an object (ring, rail, post etc).

Friction hitch. A knot that binds one rope to another and that allows for re-positioning.

Jamming. A knot that jams(difficult to untie) after use.

Non-jamming. A knot that tightens when under load, but that doesn't jam.

Loop knot. A knot used to create a closed circle.

Standing end. The part of a rope that is not made into a knot.

Working end. The part of a rope that is made into a knot.

Knots to learn to tie behind your back:

- Name: Square knot (or reef knot)

- Type: Binding(friction)

- Function: Secures a line around an object. Not suitable with lines of different diameters, not as secure as a bend(unless additional knots are used).

- Marine use: Used to secure a reef in a sail.

- Name: Sheet Bend

- Type: Bend

- Function: Joins lines of different diameters, can work loose when there is no load (for extra strength make a double sheet bend)

- Marine use: Used to extend a line, to make a tow rope, etc.

- Name: Round turn and two half-hitches

- Type: Hitch

- Function: Secures a line to a fixed object

- Marine use: Used to tie a dockline around a bull rail, or post.

- Name: Bowline

- Type: Loop

- Function: Makes a fixed loop at the end of a line. This is a non-jamming knot. With certain materials, can work its way loose when there is no load.

- Marine use: Used to secure the working end of a sheet to the clew of a headsail.

- Name: Double fisherman's knot

- Type: Bend

- Function: Makes a secure closed loop. This knot is made up of 2 knots that slide together when tightened, to form the final knot (kids use this knot to make simple adjustable bracelets).

- Marine use: Used to make a closed loop to use with a prusik knot to climb the mast.

- Name: Rolling hitch

- Type: Hitch

- Function: Used to tie one rope to another, or to a pole, for lengthwise pull along an object rather than for a pull at right angles (works for a single direction of pull). It is effective for moderate loads, won't hold as well with modern slippery synthetic ropes (use gripping sailor's hitch instead).

- Marine use: Used to pull a line lengthwise, say to take pressure off a sheet in the event of a jam.

- Name: Gripping sailor's hitch

- Type: Hitch

- Function: Used to tie a rope to an object, or to another rope. This knot doesn't jam, and won't slip when pulled lengthwise along the object. It has more grip than a rolling hitch, even on tapered objects and performs well with synthetic ropes.

- Marine use: Used to pull a line lengthwise with a heavy load at the end, like an anchor rode.

- Name: Prusik knot

- Type: Hitch, binding(friction).

- Function: Used to attach a loop of cord around a rope, it locks onto the rope when under load, but slips up and down well when the load is released.

- Marine use: Used instead of ascenders to climb a mast, doesn't damage the rope it is secured to when sliding.

safety gear

They who let the sea lull them into a sense of security is in very grave danger. — Hammond Ines

Things can happen, even on a calm ocean, so it is necessary to be alert and to not underestimate the water's strength and unpredictability. Never be complacent, and don't trust the sea.

Safety gear with auto-inflating systems need to be inspected often, and you must carry spares. Safety gear will last you many years if serviced regularly.

Pyrotechnic signaling devices (including aerial flares and hand held signals) expire 42 months after the date of manufacture in accordance with the Coast Guard requirements. Typically, this means that you must replace your flares every three boating seasons. Aerial flares cost $75 per pack of 6 (in Canada), for a boat our size (10 m) we need to have 12 aboard.

Life jackets. Wear a life jacket (with a sailing harness) and tether (especially when night sailing). The jackets need to be serviced every 3 years, so that the auto-inflating canisters can be tested, and replaced. Replacement cartridges for auto-inflating PFDs cost about $35 CAD. If planning to travel for many years out of the country, carry replacement cartridges onboard, because other countries may not carry the ones required by your model and that replacements can't be shipped by air since they're pressurized.

Life jackets that are not auto-inflating are fine, but must have a sailing harness to which you can clip a short tether. If the tether is short enough, you won't fall overboard and won't require extra flotation. Floating life jackets that are non-inflating are bulky, and may make it difficult, or uncomfortable to sail in. Wearing a short tether that keeps you to the boat, and prevents you from falling too far overboard is your best security. We recommend a short tether with two clips, so you can clip to another point on the boat while always being clipped on elsewhere.

life rafts. Re-packing a liferaft is very expensive, and varies depending on the model, and your location in the world.

Jacklines. Run jacklines along the deck, from the bow to stern cleats, and keep them within the standing rigging. Make sure the jacklines are flat, and brightly colorful so as to be visible at night. Rope jacklines can trip you up. An even better option for jacklines, is to keep them running as close to the center of the boat as possible, so that there is no chance of falling overboard when attached. Jacklines have to be made from a strong, UV resistant material, you can buy them, but we had ours made.

first aid kit

Basic First-aid kit:

Clearly mark the first-aid kit with a red cross, and make sure everyone aboards knows where it is. Keep a list inside of the items you use, and be sure to top off the kit every year or so. Also, see ditch bag.

- Sterile gauze pads (dressings) in small and large squares to place over wounds

- Medical tape

- Roller and triangular bandages to hold dressings in place or to make an arm sling

- Adhesive bandages in assorted sizes

- Scissors

- Tweezers

- Safety pins

- Instant ice packs

- Disposable non-latex gloves(such as surgical or examination gloves)

- Flashlight(with extra batteries in a separate bag)

- Antiseptic wipes or soap

- Pencil (and sharpie) and pad

- Emergency blanket

- Eye patches

- Thermometer

- A first aid manual

Basic Medicine kit:

Always read about a medicine before using it. If administering medicine to another person, ask about their allergies, and past medical history, last oral intake etc. Some medicines can cause severe allergic reactions, or may interact with other medicine.

Never administer anything to anyone without their consent.

- Ibuprofen (Oral. Minor pain, and fever reducer, e.g., toothache, menstruation cramps, headache)

- Aspirin (Oral. Pain, fever, inflammation reducer, e.g., treat/prevent heart attacks, strokes, chest pain)

- Antihistamines (allergy relief)

- Seasickness meds (scopolamine patches, dimenhydrinate(dramamine) etc)

- Ear drops

- Eye wash

- Insect repellant (mosquitoes can carry malaria, or dengue)

- Hand sanitizer

- Topical anesthetic

- Zithromycin (Oral. Treatment of bacterial infections, e.g., traveler's diarrhea, gastrointestinal infections etc)

- Oxycodone/Acetaminophen (Oral. Severe pain relief, fever reducer)

- Sunscreen (SPF 30)

- Aloe vera gel with lidocaine (for burn relief)

- Bacitracin/Polysporin/Neosporine (Topical ointment. Prevents infection. For minor scrapes, cuts, and burns)

- Hydrogen peroxide

- Imodium (anti-diarrhea)

Advanced Medicine kit add-ons:

- Hot water bottle (for hypothermia)

- Staple gun (for wounds)

- Epinephrine (vials, or Allerject/AUVI-Q. Avoid EpiPens, they are grifters)

- Tourniquet

- Multitool

- Compression bandage

- Reinforced sterile skin closures

- CPR pocket mask

- Povidone surgical scrubs (iodine)

- Sterile sutures thread with needle

- Emergency dental kit

ditch bag

Every boat should have a ditch bag, that is, a bag filled with emergency supplies in case the boat needs to be abandoned. Remember though, you should only ever have to step UP into a liferaft. Don't be too quick to abandon your boat, boarding a liferaft ought to be a last resort. In a panic, sailors board their liferafts too soon, with their boat found later, still afloat.

The ditch bag should have:

- A handheld vhf

- Spare batteries

- Noise-producing device (whistle, horn)

- Flashlight

- Water rations (4L/week for 2 ppl)

- Calorie-dense food rations (ex: 280-400 cal energy bars)

- Charts

- A good knife

- Multitool

- Sextant

- Sunscreen (SPF 30)

- Lighter & 1 pack of waterproof matches

- first aid kit

- Fish line & fish hooks

- Mirror

- Compass

- Duct tape

- Flare gun

- Emergency blanket

- Tarp, for sun protection & as vapor barrier for a hypothermia wrap(see medical).

- PLB(personal locator beacon), or EPIRB

offshore

If you want to go offshore, there is a long list of safety items, tools and spares that you need to have. Read our offshore checklist. Make sure your boat is outfitted with all that is listed, and that your boat has all of the recommended safety features before leaving.

Here's a few quick tips for offshore sailing.

- Anything on deck is sacrificial.

- In heavy winds, heave-to, don't run.

- When tired, heave-to, don't push too hard.

- Learn how to self-steer without external devices.

- Buy a good set of oil skins.

- In the cold, wear wool, not synthetics.

- Store main anchor below decks.

- Secure all floorboards and doors.

Before every long passage, we do a thorough check of all equipment on board, this means looking at the stitching on the sails, testing the electronics, checking the running and standing rigging etc. For the first time, have someone with you to help, you can also hire professionals to inspect your boat. For example, we hired a rigger to inspect Pino's standing rigging when we were planning to go offshore for the first time. We asked him a lot of questions, watched how he did things etc.

insurance

When insuring your boat, you can insure it fully, or you can get liability insurance.

Full insurance. If you hit a rock and damage your keel, full insurance will cover the work, and even the tow to the nearest facility, it will also cover the cost of salvaging it if the vessel sinks. The insurer may not cover sailing in certain areas, especially if outside of protected waters.

Getting full insurance for offshore sailing is possible but expensive, and they have strict requirements. For instance, we met many sailors in Tonga who had a 'leave by date' to sail to New Zealand. This date marked the official start of cyclone season. If they left past this date and something happened to their boat, then their insurance would not have covered the costs. This practice is unfortunate, and downright dangerous, but it is how insurers protect themselves.

Liability insurance. This type of insurance is required if you want to dock anywhere, its purpose is to cover costs if the boat damages facilities or other boats. Even when cruising the world, most places will require it, but it is often better (and cheaper) to purchase it locally—we did this in New Zealand, and in Mexico.

In both cases, your boat will need a survey to get insurance. A full out-of-water survey is required for full insurance. Some companies in Canada ask that boats older than 12 years old be surveyed every 5 years, but wooden boats need a survey every 3 years. An in-water survey may be enough for liability, but it depends on the age of the boat.

Survey

What happens when a surveyor comes to your boat? A surveyor for insurance will look at different things than one for the purchase of a boat, what they care about most is if the vessel is seaworthy. They will check thruhulls, shaft seals, keel bolts, electrical connections, battery setup, check the interior wood for water stains (indicative of water seepage, rot), engine mounts, chain plates, bilge pumps, etc.

Out of water. During an out of water survey, the surveyor will sound the hull with a hammer (tap test) to check for water instruction in the core. They will check the keel, hull for damage or osmosis. There can be surface osmosis (under paint, not severe), or hull osmosis (more severe). They will check your rudder, its alignment, and whether it wobbles or not. They'll also look at thru-hulls.

Empty the boat.If living aboard, you'll have to clear all lockers and surfaces so that they can look through every compartment without having to move anything to get to it (common courtesy). Many surveyors don't want to survey liveaboard boats because people don't want to do this, which makes it very difficult for them to do their work.

Thoughts

We sailed offshore without insurance from 2016 to 2021, because we did not have enough sailing experience and no one wanted to insure us. It was risky, but we sailed with caution. Keeping an eye on the weather, studying charts carefully, picking good anchorages, and having a good rode and anchor was our best possible insurance, but there are dangers that are beyond anyone's control, dangers that even the most skilled sailor cannot avoid, e.g., a shipping container adrift, dead heads at night, whales, etc.

A downside to insurance companies is that they are slowly pricing out small yacht owners. A machinist may not want to help a non-insured sailor with a small fix, because they can charge more to those with it. Small scale projects are not big money makers, and they are more likely to refuse them.